Recent news reports suggest that the LDP is planning to propose doubling the JET Program in three years and placing JET language assistants in *all* elementary, middle, and high schools within a decade. There are around 38,000 such schools in Japan, so that’s a LOT of ALTs!

According to internal affairs ministry statistics, in fiscal 2012 there were around 4,300 JETs in the country, so the plan is apparently to increase that by a whopping factor of nine. According to the statistics that METI keeps on language schools, there are 10,000 or so full- and part-time language teachers working for regulated schools. I believe that does not count the large number of contractors like the teachers working for ALT placement agencies or the poor devils at Gaba, university instructors, and certainly not the many student teachers or anyone operating their own eikaiwa that does not fall under METI’s purview. But even generously allowing for a teacher population of say 30,000 total (around 3 for every train station), in ten years this number will be more than doubled.

The program is designed to place youthful foreigners, generally native English speakers, in Japanese schools (and to a smaller extent, local governments) for up to five years with two explicit goals: supplement English-language education and promote international interaction at the local level. Another key benefit is that the participants often go on to take influential Japan-related jobs, be it in foreign governments, Japanese companies, or companies that do business in or with Japan. Having a stable of Japan hands around seems pretty necessary at this point, given the relatively poor state of English language ability among the Japanese population. Unlike normal employment situations, JET offers a high level of support in the form of a reasonable salary, free housing, and a network of fellow JETs and regional coordinators to help with problems.

I get the feeling that a ninefold increase in the JET Program isn’t realistic — could they even recruit that many people to come and live in Japan, or would they maybe just cannibalize the entire existing eikaiwa-for-kids market? Still, *some* increase in the program along these line seems like a fairly simple way for the Abe administration to make a bold move in the direction of “internationalization” that won’t run into much political resistance.

Regardless of your views on the merits of the JET Program or the Japanese education system in general, you must admit that even just doubling the size of JET would have a pretty profound impact.

For one thing, that is double the amount of people coming in each year. That means more foreign faces on the street and more non-Asian foreign exposure for the Japanese public at large.

It also means more “Japan hands,” maybe even double, and this can cut in different ways. I feel like Japan is sorely in need of talented Japanese-to-English translators, so an influx of native English talent that could eventually progress to ace-translator status is a good thing. At the same time, the increased supply in the market could put pressure on prices, and who knows maybe some whipper snapper could come after my job some day.

I think it would also revive the option of teaching English in Japan for graduates of US universities that (from my admittedly limited perspective) seems to have died down a bit in the wake of troubles in the eikaiwa market and competition from China, a bigger and perhaps more intriguing destination. I can envision a near future in which young men see the Tokyo Vice movie and become inspired to chase thrills and excitement in Japan.

And it would necessarily boost the number of international marriages and the resulting children, bringing Japan that much closer to becoming the Grey Race.

On the negative side, the JET Program might have to loosen standards to attract talent. Even if they don’t, the sheer number of additional people will likely result in an increase in the problems that occasionally befall foreigners in Japan – crime, drugs, suspicious visa activity, ill-advised YouTube rants, you name it.

JET is a net good, but not for Japanese people’s English ability

I say bring it on, mainly to bolster Japan-related talent. Unfortunately, my support of the program is not for its value as an English teaching tool (disclosure: my application for the JET Program was in fact rejected. I am not bitter about it because I handed in a terrible application, but nevertheless I feel like I should own up about it).

I have spoken with/read about perhaps dozens of JET teachers and students over the years. The teachers by and large do not have a particularly high opinion of the job’s value in terms of English teaching, but they almost unanimously credit the program for giving them a great experience. And while the students might not master English thanks to their JET, in many cases they remember them being a friendly adult who helped make school more enjoyable.

From what I gather, the job of an ALT is generally to supplement a Japanese teacher of English by helping with pronunciation and various other tasks. Maybe I just don’t get around enough, but I cannot recall ever hearing someone even try to argue that they are an essential part of the learning process or that what they do has an appreciable benefit to the level of English ability in Japan. I don’t think that is really a problem though because of the program’s other upsides.

On the other hand, what I have heard and experienced is that ALTs can help inspire students to discover the joys and rewards of learning English or encourage them to keep going. I think the value of that should not be underestimated because it is life-changing and the ALTs deserve huge credit for it.

This is kind of an aside, but basically I do not share the government’s fascination with trying to make the entire country proficient in English because for most people that is just not necessary. The way things stand, the biggest result of the current system seems to be the long list of Japanized English loan words that are often such a headache-inducing component of the Japanese language.

To have a more realistic and beneficial impact, I would rather them focus on establishing separate programs for the kids who excel at languages and giving them a place to shine on their own (and while they’re at it they should devote resources to helping returnees re-integrate when they come back while maintaining their language skills). That would hold out the hope of producing a larger population of Japanese adults with near-native English skills.

I feel like there is negative feedback loop whereby most Japanese people are in an environment where the norm is to not be good at English and therefore most people choose the path of least resistance. Separating out the kids that have a real talent and placing them in a more encouraging environment might keep them from missing out just because they have to go along with the crowd.

All in all, JET seems like a worthy program for giving kids a glimpse at a world outside of Japan and the teachers an interesting start to their post-college lives in a way that usually ends up benefiting Japan in some way.

PS: This independent video guide to the JET Program is very well done. If you are reading this and considering doing the program yourself, it is definitely worth a look:

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty.

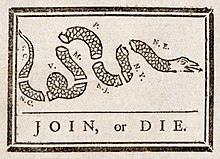

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty. And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

One of the more entertaining characters I’ve run across in my studies of Taiwan is has been

One of the more entertaining characters I’ve run across in my studies of Taiwan is has been