Anyone who follows me on Twitter may know that I have been a huge fan of the New York Times online series “Disunion”, in which a number of historians take turns writing essays about the American Civil War in largely chronological order – laid out on a great interactive timeline that offers links to contemporary articles on one screen, and links to new essays by historians on a parallel screen.

On top of the generally high quality of the writing and the presentation of lesser known but fascinating anecdotes and characters, the real time nature of the project makes it particularly interesting. When reading history it is all too easy to skim over the happenings of months or years with no appreciation that people at the time experienced them with just as much ambiguity and complexity as we experience current events today.

I don’t know how many people are actually reading the whole thing, but I have just been taking a few hours to read through the entire archive and I must say that this would form the basis for an excellent Civil War curriculum in say, a high school AP or undergraduate US History course and I am sure that more than a few teachers will be using it.

While I don’t feel like just listing my favorite posts from the series, I must point out the proposal of New York City mayor Fernando Wood to secede along with the Southern States, but instead form an independent city-state with the peculiar name of “the Free City of Tri-Insula.”

Entries such as this profile of William Webb, a slave man and underground political activist, or this one on the slaves’ view of Abraham Lincoln are also a necessarily supplement to the admittedly excellent posts on the all-white statesmen and mostly-white soldiers.

As a photography enthusiast I also very much enjoyed this post on photography in the Civil War, in particular its very first photographer – George S. Cook – who took portraits of Major Robert Anderson and his men at Fort Sumter shortly before they were attacked. Cook’s two photos below, of Union ironclads firing on Fort Moultrie in South Carolina on September 8, 1863 are believed to be the world’s first photographs of combat. Perhaps most astonishingly of all, the pair of images seem to have been intended for viewing in 3D, with a stereopticon! (There is also a slideshow of his work.)

But the single detail that jumped out at me the most is, oddly, the obverse of the banner for the “Wilcox True Blues,” a company in the Confederate military from Alabama.

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty.

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty.

And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

This appears to have been a variant on, and reference to, a proposed design for a Republic of Alabama flag during the brief period between the decision to secede and the formal creation of the Confederacy.

![]()

Students of European art history may be familiar with this phrase as the title of a painting by the Italian Renaissance artist Correggio. Those same art historians, or well-studied Catholics, may be familiar with the original source of the phrase, below as explained in Wikipedia.

Noli me tangere, meaning “don’t touch me” / “touch me not”, is the Latin version of words spoken, according to John 20:17, by Jesus to Mary Magdalene when she recognizes him after his resurrection.

The original phrase, Μή μου ἅπτου (mê mou haptou), in the Gospel of John, which was written in Greek, is better represented in translation as “cease holding on to me” or “stop clinging to me”.

Doing a quick search through books published before the Civil War shows that Noli me tangere was also the name of both a kind of skin disease sometimes associated with either lupus or cancer and a type of flowering plant. In 1719 it probably seemed common sense to name a skin disease “touch me not” and according to our 1802 botanical guide: “The elastic valves of the capsule, when ripe, curl up, and fly asunder on the slightest touch, whence the common name Touch me not.”

<iframe frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” style=”border:0px” src=”http://books.google.com/books?id=pEEPAAAAYAAJ&dq=noli%20me%20tangere&pg=PA937-IA1&output=embed” width=500 height=500></iframe>

Before considering exactly why the slogan noli mi tangere was used on the battle standard of an Alabama military unit, a glance at the books cited above and the many dozens of other search results shows that the phrase was commonly known at the time as a phrase of Biblical origin, with the literal meaning of “touch me not” as well as a number of metaphorical secondary meanings, such as for the names of diseases or plants.

Although the phrase was apparently common at the time, I would hazard a guess that it is very little known except among people familiar with the reference that made it so noteworthy to me. That is, as the title of the first of two novels by Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, whose publishing activities – especially his two novels of social protest – helped inspire the 1890s revolution against Spanish colonial rule. Originally written in the Spanish language and published in Europe with the Latin phrase Noli Me Tangere as its title, the 1887 novel came some time after the US Civil War and has no direct connection to it, but part of the symbolism of the title – “touch me not” – as an expression of defiance rings similar to its use on the Alabama flag.

Although the phrase was apparently common at the time, I would hazard a guess that it is very little known except among people familiar with the reference that made it so noteworthy to me. That is, as the title of the first of two novels by Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, whose publishing activities – especially his two novels of social protest – helped inspire the 1890s revolution against Spanish colonial rule. Originally written in the Spanish language and published in Europe with the Latin phrase Noli Me Tangere as its title, the 1887 novel came some time after the US Civil War and has no direct connection to it, but part of the symbolism of the title – “touch me not” – as an expression of defiance rings similar to its use on the Alabama flag.

Since “noli me tangere” or the English translation of “touch me not” refers to a number of plants that do grow wild in the American South I had wondered if the plant featured on the banner’s obverse might be one of them, but it is easy to verify that it is in fact a cotton plant. This is hardly a surprise, as slavery – and therefore the cotton economy – was the central reason for secession, a pillar of the state’s economy, and a cotton plant is still featured on the Standard of the Governor of Alabama (not the state flag).

Since “noli me tangere” or the English translation of “touch me not” refers to a number of plants that do grow wild in the American South I had wondered if the plant featured on the banner’s obverse might be one of them, but it is easy to verify that it is in fact a cotton plant. This is hardly a surprise, as slavery – and therefore the cotton economy – was the central reason for secession, a pillar of the state’s economy, and a cotton plant is still featured on the Standard of the Governor of Alabama (not the state flag).

The heritage of the snake, specifically a coiled rattlesnake, is probably also obvious to most Americans. This is of course a reference to the Gadsen Flag, not well known by name (I must admit I was not familiar with this name) , but well known as a symbol of the 1776 American Revolution.

“The Gadsden Flag, 1776 – The uniquely American rattlesnake became a popular symbol in the American colonies and later for the young republic. When the American Revolution began, the rattlesnake appeared on money, uniforms and various military and naval flags. To provide a striking standard for the flagship of the first commodore of the American Navy, Christopher Gadsden, an American general and statesman from South Carolina, chose the rattlesnake for

his design.”

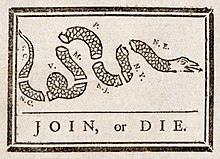

Perhaps even better known than the coiled rattlesnake image on the Gadsen Flag is the segmented snake of Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 “Join or Die” cartoon, which the Gadsen was itself referencing. But it is the coiled rattlesnake motif that the Alabama secession flag employs, and “Noli me Tangere” or “touch me not” – is obviously a reference to “Don’t Tread On Me.”

Perhaps even better known than the coiled rattlesnake image on the Gadsen Flag is the segmented snake of Benjamin Franklin’s 1754 “Join or Die” cartoon, which the Gadsen was itself referencing. But it is the coiled rattlesnake motif that the Alabama secession flag employs, and “Noli me Tangere” or “touch me not” – is obviously a reference to “Don’t Tread On Me.”

The use of the phrase Noli Me Tangere by both Jose Rizal and the State of Alabama were in the service of protest, and a move towards revolution and self governance (although Rizal was not exactly a revolutionary he did help to inspire them.) But Rizal, whose anti-colonial novel was inspired by the anti-slavery propaganda novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and preached universal freedom. Alabamans, by contrast, used the phrase to propagandize for their own freedom, but in favor of slavery – an irony that would certainly have disgusted Rizal. One imagines that had he seen this flag, rather than interpreting the snake among the cotton as a symbol of the free agrarian Confederacy, but as the Satan of slavery lurking below King Cotton’s promise. And he might have even chosen a different title for his novel.

I conclude this post with the following two minute animation, an artistic illustration of the “right” for which the Confederacy fought.

<iframe title=”YouTube video player” width=”500″ height=”405″ src=”http://www.youtube.com/embed/Tu3j7rPscpY?hd=1″ frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen></iframe>

[Update: I originally neglected to point out that the banner reads “noli mi tangere” rather than “noli me tangere,” which is simply a spelling error and of no significance that I can determine.]