I’m sure everybody reading this had been following the dramatic and confusing Chen Guangcheng1 story as it develops, and I also trust that all but the most enlightened remain as puzzled as I do regarding exactly what Chen, the United States, and Chinese authorities have negotiated, promised, lied about, achieved, failed, and intend to do regarding the still unfolding situation((Although, as I finalize this post, it does appear that Chen will be allowed to come to the US on a student visa.)).

I had certainly found the story interesting since it began, but had no particular thoughts regarding it until I read this New York Review of Books article comparing the Chen story with that of Fang Lizhi, a prominent Chinese dissident who similarly sought refuge in the US embassy following the Tiananmen Square Massacre and eventually settled in the US following similarly tense diplomacy, written by Perry Link, an American academic who was in Beijing at the time and helped Fang in his escape.

Fang, who died just under a month ago at the age of 76, after spending the latter part of his career as a professor of physics at the University of Arizona in Tucson, was a prominent dissident at the time of the 1989 protests, who sought—and received—protection at the US embassy in Beijing when the subsequent crackdown started. Before the June 4, 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, he was already well enough known to be profiled in this May, 1988 Atlantic Magazine article.

I strongly recommend reading the entire piece, as well as Fang Lizhi’s “Confession” to Deng Xiaoping, and Fang’s own commentary on writing it, which was published in June of last year, also by the New York Review of Books.

I also found Perry Link’s concluding comparison between the Fang incident and the current situation to be quite interesting.

Today, for Chen Guangcheng, the two governments might agree that exile is the least awkward solution from their points of view, but Chen may not accept it. Chinese dissidents have learned over the past two decades that exile leads to a sharp decline in a person’s ability to make a difference inside China. Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize winner who is now in his third year of an eleven-year prison sentence for “subversion,” made it clear after his arrest that he would not accept exile as an alternative to prison. From what friends of Chen in Beijing have been saying in recent days, it seems that Chen is taking a similar position.

Another important difference between the Chen and Fang cases is that Chen has a broader following among average Chinese people than Fang had. Fang was a hero to university students and some intellectuals. But most Chinese did not know him, and what they did hear of him were highly distorted accounts in the government-controlled press. Even before the 1989 crackdown, government television was broadcasting images of government-orchestrated “protests” in which farmers were burning Fang Lizhi in effigy. Many people, having no other sources on Fang, accepted such accounts. Today, though, with the Internet, far greater numbers of Chinese—millions of people including many outside of the big cities—know the true story of Chen than ever knew the story of Fang. And to judge from the many accounts circulating on microblogs and elsewhere, hardly anyone seems to view Chen with anything but sympathy.

But while it does seem likely that Chen has widespread support, I wonder what good that will do for him in America, other than provide a comfortable life for him and his family.

For example, look at how much support the dissident Chinese artist Ai Weiwei received after his own unjust arrest, almost entirely enabled by the Internet. And in his case, not only did he receive the ephemeral support of Tweets and Facebook “likes”, but enough small donations (which the artist categorized as loans to be repaid in the future) from tens of thousands of donors to cover the Chinese government’s punitive taxes and fines (which Ai and his legal team continues to challenge).

But how contingent is that support on the fact that he is staying to fight? While there is no question that Ai Weiei, by all accounts charming and brilliant, would be a darling of intellectual and artistic as a political exile, he would also lose the ability to use his own ongoing on-and-off imprisonment as fodder for political artwork such as his recent and short-lifed self-surveillance “Weiweicam” project.

While much about the Chen Guangcheng case remains murky and mysterious, he does at least seem to wrestling with such a choice. Will he stay in China, despite the risk to himself and—apparently more importantly—his family, or will he seek exile2, where he would undoubtedly be safer and more comfortable((He certainly has plenty of supporters in the US, since if there is one things that the “Pro-life” and “Pro-choice” camps can agree on wholeheartedly, it’s that forced abortions are a bad thing.)), but also risk damaging his own credibility as an activist and his ability to help others.

The NYT had an article on Friday discussing this very possibility, saying “Based on past experience, China is often all too pleased to see its most nettlesome dissidents go into exile, where they almost invariably lose their ability to grab headlines in the West and to command widespread sympathy both in China and abroad.” The article goes on to mention how “If Mr. Chen receives a green light to depart for the United States, he will arrive to find a fractured tribe of Chinese dissidents and pro-democracy advocates shouting over one another.”

This line in particular made me think of a particular book I read several years ago, which had already been on my mind as I was catching up on the past week of Chen Guangcheng related coverage earlier today, In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture, By Geremie R. Barmé. Despite the bland and vague title, a significant portion, or even a majority of the book is devoted to Chinese counterculture and dissident protest, including quite a bit of discussion of the criticism and failure that prominent Chinese dissidents have faced in exile, including from one another.

Among exiled intellectuals for a time there was also a considerable amount of critical reflection on the events of 1989. Yuan Zhiming was another of the writers of River Elegy, the television series that was branded by the government as part of a wave of “cultural nihilism” that contributed to the protests. In an article published in January 1990, Yuan questioned what would have happened in 1989 if the most famous Chinese public intellectuals — Fang Lizhi, Liu Binyan, Yan Jiaqi, Chen Yizi, and Su Xiaokang, had “courageously stood forward and led the movement.” He continues his speculation in the tone of a guilty survivor:

If we had formulated some mature, rational and feasible plan of action and organized a democratic front incorporating the students and civilians, if we had worked harmoniously together to struggle for dialogue with the authorities, how would it have turned out? Of course, we may still have been vanquished, but at least we could say we had done everything in our power to prevent defeat. 3

Barmé is also unimpressed with the post-exile efforts of dissident intellectuals, writing:

Prominent intellectuals and students had, bu the very fact of their exile, suffered a serious blow to their credibility. This was particularly so, since it was widely perceived on the mainland that many of the key agitators of 1989 had sought refuge with former imperialist powers (that is, France, England, and the United States((And we could add Japan to this list, which not only sheltered some refugees from China, but also applied pressure on the PRC government during the Fang Lizhi incident, using the carrot of development loans.))) and the KMT government in Taiwan. The mainland authorities were well aware of the jealous reaction of its people to reports of dissidents living off the fat of the land overseas, and the official media took delight in portraying them all as traitors to the nation.4

The remainder of the third chapter deals with this issue in greater depth, and I recommend it to anyone wondering how successful an activist Chen might be in exile.

Even though modern communications has greatly improved the ability of activists and supporters to coordinate better and more secretively across borders, it is hard to imagine how Chen Guangcheng, whose activism so far has largely taken the form of legal action that would be impossible to file from abroad, would be able to continue his activism in any substantial way after reaching NYU. Above, I cited speculation by a sympathetic Chinese intellectual over what would have been different had Fang Lizhi and his compatriots “courageously stood forward and led the movement” rather than accepting exile. In America, Fang was very successful in continuing his career as a physicist, but his post-exile activism was a mere footnote to the exile itself. How might Chen’s career develop if he comes to the US, and how might it develop if he does not?

- This 2006 NYT story is a good description of his career and legal troubles up to that point. [↩]

- Or asylum, or “rest”, or “study abroad”. [↩]

- Pages 51-52 [↩]

- Page 44 [↩]

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty.

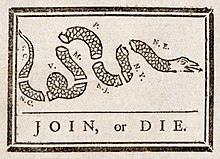

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty. And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”