Taiwanese tabloid news video makers NMA have a way of perfectly capturing the silliest and most over-the-top possible interpretations of events. Case in point, their take on Japanese herbivore-men:

The video reminded me of the emergence of a mini-trend – articles countering the familiar narrative of Japanese decline and decay. Here are a couple examples.

First, we have Foreign Policy blogger Joshua Keating, who has started a “Japocalypse Watch” to point out over-enthusiastic reports of Japan’s decline:

I’m not really sure I buy [the trend of youths wearing skinny jeans] as a response to the Japanese economy unraveling. First of all, another recent New York Times trend piece informs me that rising economic power China also has kids with tight pants.

Then there is Atlantic correspondent James Fallows, who used to live in Japan:

The broader point is that while there may be a few relatively small countries that can be classified as “failures” across the board, big complex societies are always a mix of strong and weak points, and the prevailing Western view of Japan goes way too far in (self-congratulatingly) dismissing it as an utter “failure.”

And my personal favorite is a column from David Pilling that questions the assumptions that lead people to dismiss Japan as a failure:

If one starts from a different proposition, that the business of a state is to serve its own people, the picture looks rather different, even in the narrowest economic sense. Japan’s real performance has been masked by deflation and a stagnant population. But look at real per capita income – what people in the country actually care about – and things are far less bleak.

After living in Tokyo for a few years I have become quite sympathetic with this side of the argument. It’s clear that a lot needs to be done to ensure Japan’s continued prosperity, including securing the government’s long-term finances and social safety net. But compared to even the US, there’s a lot to admire and enjoy about life in Japan. Of course, my tune could change once the government announces what will no doubt be some significant tax and withholding increases over the next year or so.

Correcting the record

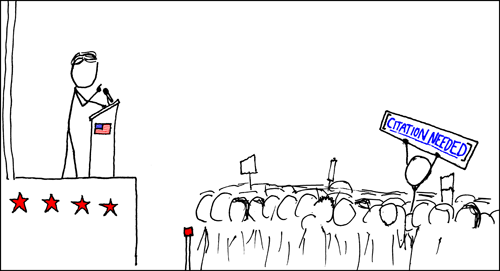

It would certainly be nice if reporters on the Japan beat didn’t approach their work with such a focus on declining vs. rising powers or other overly broad themes. Maybe articles like these will spur some reflection among correspondents, which would be a positive step.

At the same time, it’s hard to get worked up about this kind of stuff anymore. I understand that readers in New York or Washington will lose interest unless the topics stay broad and generally within their realm of familiarity. In my case, when I read about parts of the world that aren’t familiar to me, NYT articles are almost always more digestible than the local English-language news, simply because I am not familiar with the local leaders or various aspects of the culture.

Probably the best course for people with an interest in setting the record straight is to focus on communicating your side of the story and pointing out egregious errors. One\ recent example seemed like a pretty healthy exchange of ideas. The NYT’s Hiroko Tabuchi wrote an article “Japan Keeps a High Wall for Foreign Labor” that took a negative view on the Japanese government’s policy on foreign labor. In response, the Japanese embassy replied with some clarifications and rebuttals.

Merits of each argument aside, I feel like this was a perfectly appropriate and thoughtful response to an article that was basically sound. Of course, it helps when there’s a solid foundation to the article in question. There’s probably nothing you can do to counter the endless stream of Japan Weird stories.