Just came across a very cool blog from Fumi Yamazaki, who works at Digital Garage (an IT company perhaps best known for its promotion of Creative Commons licensing and Joi Ito’s involvement). She’s interested in how Japan is using the internet, so reading through her posts will give you some idea of “what’s going on in Japan right now” as the title suggests.

I wish I had found her blog sooner because I have been working on gathering together data on how Japan uses the Internet for a while now, but haven’t been sure how to present the information. But now with the development of some interesting discussion on “the state of the Japanese web” now might be appropriate for me to just dump what I have.

Connections and usage patterns

Perhaps the most authoritative survey of Japanese Internet usage is the annual Communications Usage Trend Survey from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC). Much of the information below was taken from this source. It covers a truly broad range, so I encourage people to read the English summary edition (PDF) for more details (on topics such as IP telephone usage, business Internet adoption, etc.).

PC and Internet penetration

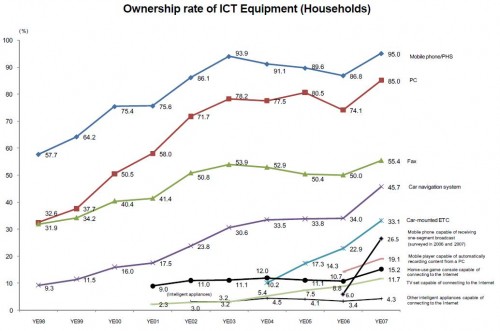

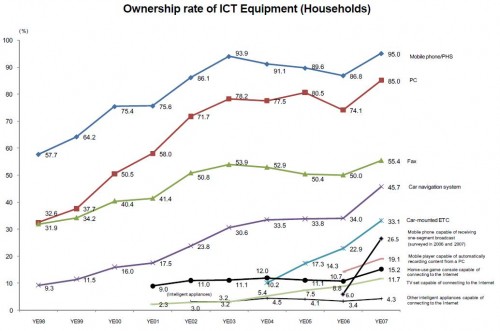

For an overall idea of what hardware is in use, the MIC has this handy breakdown of ownership rates over time (in this report, all charts were prepared by the source unless otherwise noted):

Cabinet Office data shows that 85% of Japanese households owned a PC as of March 2008, versus 98% who own at least one color TV and 95% with at least one mobile phone. This can also be compared to an estimated 76% of Americans who claimed to own PCs in 2005, a figure that likely rose since then.

Meanwhile, the MIC survey (covering both PC and mobile usage) shows that 91.3% of households reported using the Internet at least once over the past year, while 50.7% used it for personal reasons in the past month as of March 2008. However, there is reason to believe the MIC data may be overstating the real situation somewhat, as the 52.4% rate of valid responses is significantly lower than the near 100% level for Cabinet Office data. This means that the data could be biased toward people with an active interest in technology.

Number of users

Recent stats from MIC (also covered by Fumi) show that measured against the population, MIC data shows that overall 75.5%, or 90.9 million people, had used the Internet at least once over the past year, either on mobile or PC. The total is up from just 9.2% in 1997, a simple linear growth rate of about 7 million per year.

International statistics from UN body International Telecommunications Union of the number of Internet users per 100 residents show that Japan ranks in the top tier of wired nations – the 2nd highest in Asia after S. Korea, exactly even with Australia, but slightly under the US figure of 72% and well under some European nations (and I don’t think anyone can hope to approach Greenland’s 90% – that means even old people must be checking their e-mail!). I put this chart together to see how the pace of growth stacks up with some of the world’s other Internet powerhouses:

* See my Google Document for comprehensive global data from the UN-sponsored International Telecommunications Union (2000-2007).

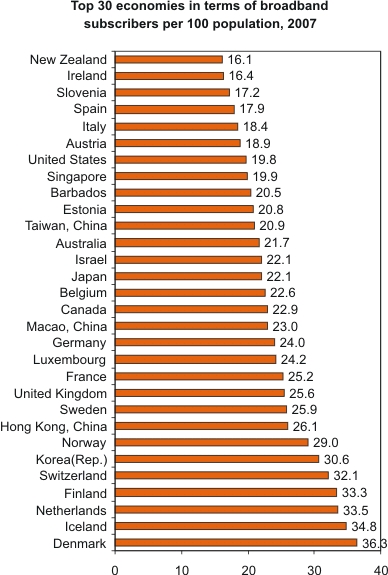

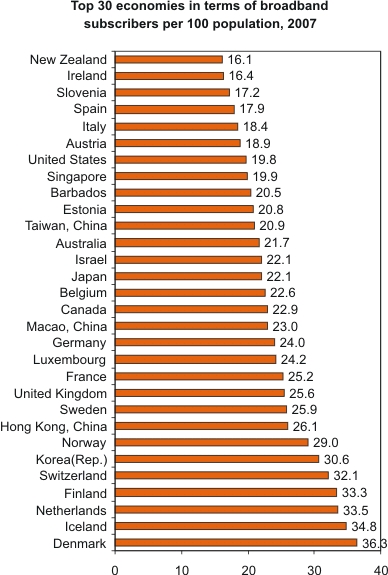

Broadband penetration

Aside from the widely debunked idea that Japanese is the language with the most blogs, one of the more famous statistics about the Japanese internet is the country’s high level of broadband penetration. Once again, this number comes from ITU, current as of 2007:

Japan comes in 17th, behind Canada and Korea but way ahead of the United States, as was true when New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman noticed in 2005, quoting from an article in Foreign Affairs, baseless claims of “top-notch political leadership” aside:

[T]he United States is the only industrialized state without an explicit national policy for promoting broadband….

[W]hen America “dropped the Internet leadership baton, Japan picked it up. In 2001, Japan was well behind the United States in the broadband race. But thanks to top-level political leadership and ambitious goals, it soon began to move ahead.

“By May 2003, a higher percentage of homes in Japan than the United States had broadband. …

“Today, nearly all Japanese have access to ‘high-speed’ broadband, with an average connection time 16 times faster than in the United States – for only about $22 a month. … And that is to say nothing of Internet access through mobile phones, an area in which Japan is even further ahead of the United States. It is now clear that Japan and its neighbors will lead the charge in high-speed broadband over the next several years.”

Interestingly, a recent study showed that 2/3 of US dial-up users (“9% of all adults”) have no intention to switch over to broadband, while in Japan it seems like there almost is no other option.

Speed and price

Data on Japan’s Internet speed and price also comes from the New York Times:

I use NTT East’s B-Flet’s service and pay somewhere around 4000 yen per month for the 100Mbps connection, something that as far as I know still isn’t available in the US except perhaps in select areas and certainly not for these prices. As far as I know, this is the common service package for most households with Internet connections.

Much of the attached 2007 article is more distracting than informative, but I’ve taken the liberty of Mad-libbing a key section for enhanced accuracy:

[T]he stock price of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone, which has two-thirds of the fiber-to-the-home market, has sunk because of concerns about heavy investments and the deep discounts it has showered on customers. Other carriers have gotten out of the business entirely, even though it is supported by government tax breaks and other incentives.

The heavy spending on fiber networks, analysts say, is typical in Japan, where big companies [are forced to] disregard short-term profit and plow billions into projects [out of deference to their regulator’s] belief that something good will necessarily follow.

Matteo Bortesi, a technology consultant at Accenture in Tokyo, compared the fiber efforts to the push for the Shinkansen bullet-train network in the 1960s, when profit was secondary to the need for faster travel. “[The internal affairs and communications ministry wants] to be the first country to have a full national fiber network, not unlike the Shinkansen years ago, even though the return on investment is unclear.”

“The Japanese [bureaucrats] think long-term,” Mr. Bortesi added. “If [the ministry thinks it can secure funding for a project they can hype as something that] will benefit in 100 years, they will [go forward with deficit spending that will be repaid by] their grandkids. There’s a bit of national pride we don’t see in the West.”

Now, I don’t want to be too cynical – the very success of this push for superior broadband access speaks well of those that promoted it, and regardless of pure intentions or what have you, this has had enormous ramifications for Japanese society and has produced an excellent technical Internet infrastructure.

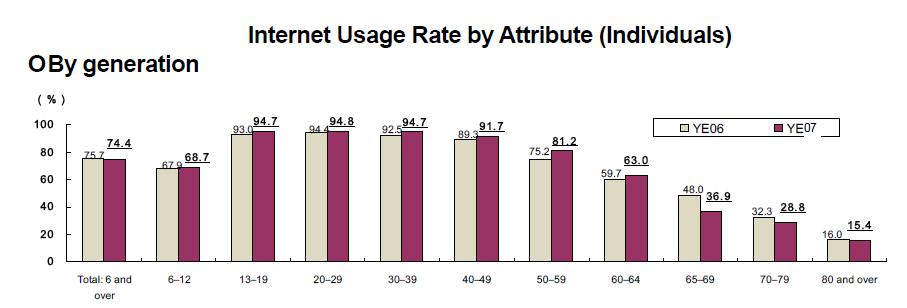

Age distribution

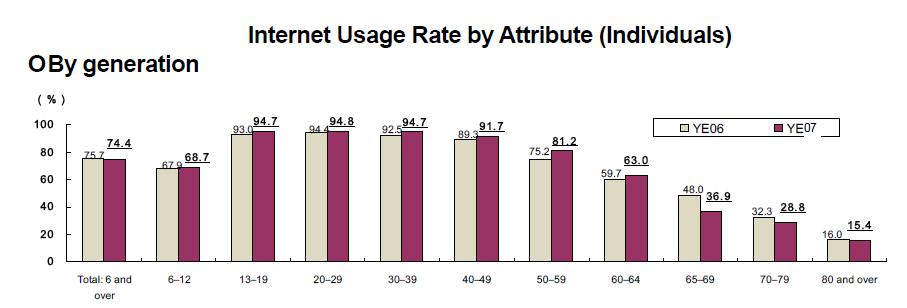

MIC data show 90% or greater Internet usage among all age groups from teens to people in their 40s, with a sharp drop to about 2/3 of people in their early 60s, 1/3 of those in their late 60s, 1/4 of 70-somethings, and 15% of people in their 80s. You’ll see that there is steady growth among the 50s and 60s age groups.

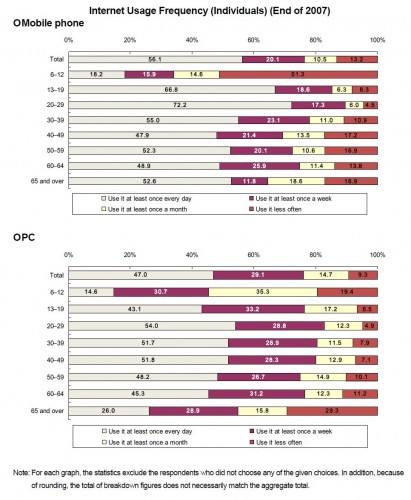

Frequency/intensity of usage

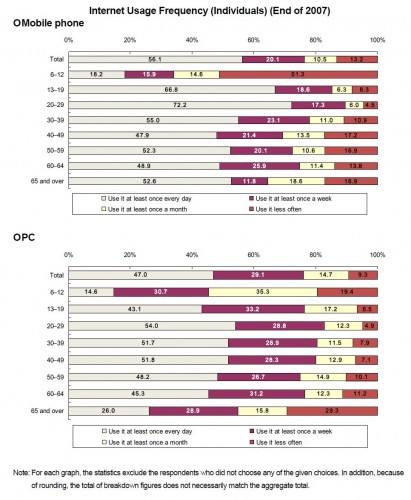

MIC data shows that 54.1% of Internet users use their mobile phones to access the Internet every day, compared to 47% of those who use a PC every day. Adding in the people who declined to respond to this question indicates that around 70% of both PC and mobile users access the Internet at least once per week.

By 2004, users were spending more time per day using the Internet than reading newspapers (TV: 3 hrs 31 min; Internet: 37 min; Newspapers: 31 min)) .

An 2007 MIC poll (graph here) found that 44.6% of people used the Internet at least once or twice a month, with the rest responding they use it “hardly at all” or “not at all.”

As for the male/female divide, it appears that significantly more men are online than women. The same MIC poll found that 35.2% of men use the net “almost every day” versus just 21.1% of women. A majority (52.7%) stated they never use the internet at all.

These overall figures are significantly skewed by the older demographics’ tendency to stay offline. More than half of people aged 20-29 use the internet almost every day, while a majority of all people aged 20-49 use it at least several times a week. These numbers drop off among those in their 50s or older.

Usage time

Two private-sector studies give an idea of how much time people in Japan spend using the Internet.

- The Hakuhodo Institute of Media Environment did a random telephone survey (PDF) in 2008 of residents of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kouchi prefectures (presumably to compare two big cities with a more rural area) to find their relationship with the six major media (TV, radio, newspapers, magazines, PC Internet, and mobile Internet). In all three areas, respondents reported using the Internet (either via PC or mobile) for more hours than any other media besides television, though TV was the overwhelming winner, beating out Internet time by a ratio of around 2:1 in Tokyo. Tokyo’s reported Internet usage time per day was 77.1 minutes (versus 161.4 minutes of TV every day).

- Internet research firm Netratings noted that total page views have fallen recently despite steady increases in overall usage time. The change comes as “rich content” such as Youtube videos have kept users at the same page longer.

Where people access – Overwhelmingly at home and work

The MIC asked respondents to answer where they have used the Internet over the past year. The top ten answers were:

- Home (85.6%)

- Work (36.6%)

- School (12.9%)

- Internet cafe (5.3%)

- Hotel or other lodging facility (5.2%)

- Public facilities (city hall, library, civic center, etc.) (4.7%)

- In transit on public transportation (2.9%)

- Airport or train station (2.2%)

- Restaurant, cafe or other dining establishment (1.7%)

- Other (1.7%)

This seems largely in line with the typical paradigm in the US and elsewhere.

People in their 20s and 30s were the most frequent in-transit Internet users (4.2% and 4.4%, respectively). The biggest in-transit demographic were men in their 30s at 6.2%.

While MIC data shows that Internet cafe usage pales in comparison to overall usage, a 2007 online survey (which will necessarily skew toward active Internet users) showed that around half of respondents had used a manga Internet cafe in the past, 20% for business purposes.

Data compiled from the receipts of Internet cafes between 2005 and 2007 by Plustar, a provider of business software for Internet cafe operators, shows that users are predominately males (70%) in their 20s and 30s.

PCs vs. Mobile

Much is made of the popularity of the mobile web in Japan, spurred on by images of trendy high school girls tapping away on their elaborately decorated keitai. It is true that Japanese consumers often suffer through long train commutes that give them time to surf online, and an infrastructure is in place simple web interfaces for the most popular sites, such as anonymous forum site 2ch and social networking giant Mixi. However, the available data is mixed on this issue, indicating that the hype could be outsized compared to actual usage. And it is highly possible that the perceived high usage of “the Internet” on mobile phones stems from Japan’s somewhat unique technology infrastructure – “text messaging” from mobile phones is all done using e-mail protocols, where in much the rest of the world it is done through SMS messaging.

The MIC tells us that while 88% of Internet users access from a PC vs. 82% with mobile phones, 68% of users use both a PC and mobile device. 16.7% of users only access from a PC, vs. 11.3% who only use a mobile device. The mobile-only population grew from just 7.9% in 2006, compared with a fall from 18 .6% for the PC-only group.

As noted above, MIC data shows that overall more people use their mobile phones every day to access the Internet, and about the same ratio use either their PC or mobile to access at least once a week. However, those surveyed appear to prefer using PCs for all Internet activities except e-mail, usually by wide margins. People also selected online shopping and purchasing online content as major purposes for using the mobile web:

Japan public opinion blog What Japan Thinks (whose author Ken Y-N I am proud to say is a regular commenter) has translated an online poll showing that users polled via mobile phone overwhelmingly use a PC as their main web conduit rather than their mobile phone (87% vs. 10%). There are important caveats to the data, such as “one way that they recruit their mobile monitors is by getting them to enter their mobile phone email address when they apply to be a PC monitor.” But the fact that it’s not even close suggests that there is something to it.

Yahoo Japan releases a breakdown of its unique page views each month for investors. The figures through January (PDF) similarly show that just 10% of their traffic comes from mobile users:

This rate of around 10% is comparable to rates in the UK and US as of June 2008, according to market research firm comScore.

***

OK, that’s about all I’ve got for now, but I hope it will serve as a starting point for discussion and future posting.

From what I see here, Japan is one of the most connected countries on the planet, and the people here use the internet, mostly on PCs, at a fairly high rate, especially the younger generation.

The next question I want to try and answer is how the Japanese people have adapted this new tool to their everyday lives (obviously there are lots of people studying this issue with intense interest, but so far I just haven’t seen a satisfactory answer). That will be for future posting. But to get started, I recommend two resources – Yamazaki’s recent post on the most popular sites for female users – unsurprisingly, social networking service Mixi topped the list); and this recent J-Cast article on the demographics of 2ch users.

(Updated – Fumi Yamazaki only used to work at Digital Garage)