Note Howard Dean’s statement toward the end of this video:

BTW, the Talking Points Memo blog’s “Day in 100 Seconds” and “Sunday Show Roundup” are great. This way I don’t have to actually watch those painful news shows.

Note Howard Dean’s statement toward the end of this video:

BTW, the Talking Points Memo blog’s “Day in 100 Seconds” and “Sunday Show Roundup” are great. This way I don’t have to actually watch those painful news shows.

On Tuesday, parts of Japan’s political net-osphere will go dark as the official campaigning period begins for the August 30 general election to select members of the nation’s lower house of parliament. Considering that this election has the potential to take government control away from the ruling Liberal Democratic Party for the first time in 13 years, national and international attention on this race is high.

So what can I add to the conversation? My interest in Japanese politics and other current events is fairly intense, so I plan to follow this story with the same rigor I apply to my other favorite topics.

Mainly, I plan to profile the candidates up for election in my district (Tokyo’s 13th) to give a worm’s-eye-view of the election from my perch in Adachi-ku, Tokyo. Some readers will recall my series of candidate profiles leading up to last month’s Tokyo prefectural assembly elections.

But first, some opening remarks:

What will this election decide?

On Sunday, August 30, Japanese voters will go to the polls to elect all 480 members of the House of Representatives, the more powerful house of the country’s bicameral legislative branch of government. After the election, the Diet (Japan’s word for its parliament) will be convened to choose a prime minister, who will then form a cabinet. The upper and lower house will each conduct a vote, but if the upper house vote differs from the lower house’s, the lower house’s choice will prevail. If one party has won an outright majority of seats in the lower house, it can elect a prime minister without the aid of any other party, but if not various parties will have to negotiate and form a coalition government.

The lower house is where most substantive legislative business is done. It controls the passage of the national budget, can override an upper house veto with a two-thirds vote, and most importantly decides the appointment of the prime minister. The DPJ currently controls the upper house, which is a less powerful but still significant part of the legislative process.

The party (or coalition of parties) that wins this election will ostensibly gain control over essentially the entire country — if the DPJ gains control it will preside over the executive branch, dominate both houses of the legislature, and possess the power to appoint Supreme Court and lower court justices.

In practice, however, the prime minister and cabinet’s power has been limited – to give a very broad outline, powerful ministries set the agenda on most important national issues, the legislature exists mainly to ratify that agenda and distract the public with loud but ineffectual drama and scandal (in exchange for funneling money back to their districts), and the judicial nominees are almost never decided by the elected officials themselves.

The opposition Democratic Party of Japan are on track to make significant gains in this election, though it will be a tall order to increase their current standings (110) to exceed the LDP’s total of 303. The DPJ are campaigning on many issues, but perhaps first and foremost on a revolutionary vision of administrative reform. They believe that the bureaucrats in the country maintain power based on, in Secretary General Acting President Naoto Kan’s words, a “mistaken interpretation of the Constitution” that bureaucracy has the inherent right to control government administration, while it’s the job of the cabinet and legislature concentrate on passing laws. The DPJ would like to wrest control away from the “iron triangle” of unelected bureaucrats, powerful business interests, and their cronies in the Diet and place power squarely in the politicians’ hands. But more on that later.

How are members selected?

Since the law was changed in 1993 following a major LDP electoral defeat, members of Japan’s lower house have been chosen using two parallel systems – 300 are selected through single-member districts nationwide similar to the US House of Representatives, while the remaining 180 seats are allotted through a proportional representation system (or PR for short).

Under Japan’s PR system, the parties running in the election field candidates in each of 11 regions. On election day, voters write down two votes for the lower house – one for their preferred individual in their district, and the other to choose a party they’d like to receive the PR seats in their region. In the interest of counting as many votes as possible, votes will still count if a voter writes in the name of an individual running in the region or the party leader’s name instead of the party name.

For example of how this works, in 2005 the Tokyo PR district had 17 available seats. To win a seat, a party would have had to earn at least 5.88% of the vote, or 389,682 votes. Only one party that ran (Shinto Nippon with 290,027 votes) failed to gain a seat in this district.

The fact that relatively fewer votes are needed to win a PR seat has convinced smaller parties to try their luck. Most recently, the Happiness Realization Party, a newly formed political wing of new religion Happy Science, has decided to field more than 300 candidates in all single-member and PR districts (though as of this writing it is unclear whether they will actually go through with it). The religion’s leader Ryuho Okawa has announced his intention to run in the Kinki PR district with the top position. To do so he will need 3.45% of the vote, which would have been around 375,000 votes in 2005. His party would have to seriously improve its performance after winning a dismal 0.682% (13,401 votes in 10 districts) of votes in the Tokyo prefectural elections. Okawa had originally planned to run in Tokyo, but Tokyo has a higher 5.88% hurdle to overcome.

How does voting work in practice?

After entering the polling station, voters will be handed a paper ballot and a pencil (yes, a pencil, not a pen). They will be directed to a table with a list of candidates and instructions on how to vote. There they will write in the name of their preferred candidate along with their PR vote. To make it easier for voters to remember, many candidates spell their names using phonetic hiragana instead of kanji, which can be harder to write and have many different readings.

Since this election will also include a people’s review of nine of Japan’s 15 Supreme Court justices, voters will be required to mark an X next to the names of justices they would like to see dismissed. Blank votes will be counted as in favor of keeping them on.

In my next post, I’ll talk about the issues and outlook for this specific election before getting into the more provincial task of profiling my local candidates.

(Updated with correction, thanks to Curzon)

Everyone knows that Japan’s lower house of parliament is up for re-election on Sunday, August 30.

But what you may not have heard is that some Supreme Court justices are also up for a “people’s review” (国民審査) at the same time.

Thanks to a banner on the sidebar of Yahoo Japan’s politics site, I now know how this works:

On paper, Supreme Court justices are “appointed by the emperor” based on the cabinet’s nomination and thus the Chief Justice serves as a minister of the emperor on the same level as the prime minister. However, the Japanese emperor has no real power, so in fact this means the justices are appointed by cabinet decision.

As a means of providing a democratic check over the judicial process, each justice is subject under the constitution to a people’s review at the general election immediately following their appointment, and then again every decade thereafter. In the upcoming election nine of the fifteen justices are up for review, including Chief Justice Hironobu Takesaki who was appointed by the Aso cabinet in November 2008.

At the polls, voters will be presented with a ballot listing the name of each justice with a box next to each name. The voter must place an X in the box to affirmatively vote to dismiss each judge. Blank votes are counted as votes in favor.

As far as I can tell, this system is all but window-dressing. So far, no judge has ever been dismissed in this manner, and among current justices who have undergone review, the justice with the highest ratio of votes against him is Yuki Furuta at 8.2%.

This appears to be the only way for the electorate (or their representatives) to dismiss Supreme Court justices, though there is The other ways that justices can be dismissed are the age requirement (they must retire by their 70th birthday) and a law that judges can be tried for dereliction of duties or other misconduct in the Court of Impeachment, consisting of 14 lower and upper house MPs (no Supreme Court justice has ever been impeached).

The Supreme Court‘s English-language page has a very brief mention of this system toward the bottom:

The appointment of Justices of the Supreme Court is reviewed by the people at the first general election of members of the House of Representatives following their appointment. The review continues to be held every ten years at general elections.

A Justice will be dismissed if the majority of the voters favors his/her dismissal. So far, however, no Justice has ever been dismissed by the review.

Justices of the Supreme Court must retire at the age of 70.

The Japan Times had a good Q&A about the Supreme Court back in September 2008.

Thanks to Gen Kanai for passing on this landmark lecture on Youtube culture and how it’s turning all Americans into attention whores who can only find validation through media exposure:

This appears to be on the same page as J Smooth’s observations about how even as the Youtube generation mourns Michael Jackson’s death, now that everyone is a media star they must deal with the same pressures of public exposure that Jackson faced:

I am currently reading Discrimination and Power (差別と権力), Akira Uozumi’s fascinating biography of Hiromu Nonaka, a former LDP heavyweight and cabinet minister known as a member of the burakumin, a minority outcast group who have suffered discrimination due to their historical role in feudal Japan as leather tanners and undertakers, vocations considered unclean. MFT readers will remember him as the man a New York Times article characterized as Japan’s version of Obama, as he too was a minority politician who rose to become a powerful politician.

I will post more on the book later, but for now I just want to share the following episode:

Just four months after Nonaka’s first successful bid* for the Diet’s lower house in 1983, the Kyoto Prefectural Police arrested the head of his koenkai (support association, kind of like a political action committee) for violating election laws. But Nonaka and associates were mostly able to beat the charges. Here is why:

You see, when Nonaka was first elected to the lower house he was already 57, a very late start for an LDP politician. But before that he had already made a very large name for himself in Kyoto prefectural politics as an anti-Communist conservative at a time when Kyoto had a Communist governor for more than two decades.

Part of the secret of Nonaka’s success was a questionable election tactic – when election season came around, construction executives friendly with Nonaka would mobilize housewives associations and other support groups to visit houses and run “get out the vote” campaigns in Nonaka’s home district of Sonobe and surrounding areas of Kyoto. Under Japanese election laws it was (and remains) illegal for politicians or their staff to visit people’s homes to ask for support, as it’s (correctly) assumed bribes will be forthcoming during such visits. However, Nonaka was able to get away with this for years as the construction executives ostensibly acted independently.

Eventually, police found evidence that during Nonaka’s first bid for the Diet, the voter mobilization efforts were in fact illegally run directly by the campaign. That’s when they moved to raid Nonaka’s offices, arrest the head of the koenkai, and question two leaders of the koenkai‘s youth bureau.

However, the charges never stuck due to a lack of evidence or confessions (subordinates were prosecuted for minor offenses but the investigation never spread) thanks to a flurry of expert moves by Nonaka’s people to undermine the investigation before, during, and after the fact. They included:

From the beginning, the top brass in the police were hesitant to rock the boat since the politicians have a hand in deciding the police force’s budget. I can’t help but think they were a little prescient.

*from Kyoto’s 2nd district; he ran with (or more appropriately, against) Sadakazu Tanigaki and they each won a seat in the two-member district.

(Updated)

A few weeks ago NYT ran this great article about the difficulties of raising a son in both Japanese and American cultures:

My Un-American Son

By KUMIKO MAKIHARA

Getting Yataro ready for his first sleep-away camp overseas is turning out to be much more than counting T-shirts and towels. I’m having to review the way children interact here to see which behaviors would go against American codes of conduct. American parents have higher standards than Japanese when it comes to acceptable behavior among children.

Take “kancho” for instance, a popular prank where kids creep up on and poke each other with pointed finger in the behind, shouting “kancho!” or enema. That would likely have the camp counselors in America alleging sexual abuse.

Kancho certainly isn’t encouraged in Japan — a friend of mine is convinced her daughter failed a preschool entrance exam because she playfully jabbed her mother in the rear during the interview. But Japanese parents usually bestow only a mild rebuke.

Please head on over to NYT to read the original article!

Other differences mentioned:

All these observations ring very true, though obviously your mileage may vary. I thank my lucky stars every day that I’ve never been kancho’d.

What I like best about this piece is that she resists the temptation to theorize or lecture about which society has the better practices. That’s the right approach because proclaiming one country’s education/child-rearing regime to be superior to the other’s does nothing to help Yataro navigate his new summer camp. By talking from her own experiences as someone who has had to navigate both societies (and offering some speculation about how Americans at the summer camp will react), she is able to shed light on cultural differences without getting into ultimately unhelpful broad conclusions. And in the process she has given us an entertaining and enlightening case study in the form of her own son. I look forward to the follow up article to hear how Yataro fared.

(A Google search for “Maki Katahira” “Kumiko Makihara” reveals several other articles about her son and life in Japan, along with this right-wing conspiracy theorist who implies she must be a CIA agent and part of the Trilateral Commission‘s plot to control Japan because she was married to former Newsweek Japan bureau chief William Powell (though apparently they divorced) and once worked as an executive assistant for a firm partially owned by private equity group Ripplewood. I don’t want to lend any credibility to this crackpot, but even if she is working for the man, this is still a pretty great article)

Most of our readers are aware that, when written horizontally, Japanese is generally read left to right. When written vertically, as was the traditional method, paragraphs start on the right and each line is read down the page in order from right to left. Traditionally, though, Japanese and Chinese were both read right to left at all times, even when written horizontally.

The history behind this is kind of interesting. Here’s a timeline culled from the Japanese Wikipedia article on the subject.

* Traditionally, Japanese was written vertically, and lines were read from right to left. Horizontal writing only appeared on signs, and in those cases it was also read from right to left.

* Horizontal writing first appeared in print in the late 1700s as Dutch books were reprinted. (Dutch traders in Nagasaki were the only Europeans allowed in Japan at that time.) In 1806, a Japanese book was published in Japanese hiragana characters skewed to look like Latin characters and printed from left to right.

* In the first foreign language dictionaries printed in Japan, foreign words were written horizontally from left to right, while the Japanese words were written vertically from top to bottom. The first dictionary to have both foreign and Japanese words written horizontally came out in 1885, and both were written left to right.

* Japan’s first printed newspapers and advertisements had headlines and call-outs written horizontally from right to left.

* In July 1942, at the height of World War II, the Education Ministry proposed that horizontal writing be from left to right rather than from right to left. Although the left-to-right standard was showing up in some publications at the time, switching over entirely was a controversial idea which didn’t make it past Cabinet approval.

* The military also tried adopting left-to-right as an official standard during the war, but many people viewed this as too Anglo-American and refused to switch.

* Because of the patriotic zeal surrounding text direction during the war, there were cases of stores being pressed to switch text direction on their signage, and cases of newspapers refusing to print advertising with left-to-right text.

* After the war, Douglas MacArthur’s occupation team pushed for left-to-right text as an education modernization reform measure, along with the abolition of Chinese characters and other more extreme ideas.

* Yomiuri Shimbun was the first newspaper to switch text direction in its headlines, making the changeover on January 1, 1946. The Nikkei switched over by 1948.

* Japanese currency was first printed with left-to-right text in March 1948; before that, it had been printed right-to-left.

* Asahi Shimbun conducted some internal design experiments around 1950 to switch its front page to an all-horizontal, left-to-right format, but this never made it past the drawing board.

* In April 1952, the Chief Cabinet Secretary adopted a guideline that all ministry documents be written from left to right using horizontal text. Despite this, the courts kept vertical writing until January 1, 2001–the bar exam was also written vertically until that time–and the Diet itself continues to use vertical writing when publishing draft bills.

Right-to-left writing is still found in certain contexts. Sometimes it is used simply to appear more “traditional”: Wikipedia cites soba shops as a common culprit in this category. Another common context is vehicles such as trucks and ships; there, Japanese is often written from front to back, so on the right side of the vehicle it is written from right to left. Here’s an example which I spotted on a right-wing sound truck outside Odakyu in Shinjuku during my first trip to Tokyo, way back in 2000. Note that the text 愛国党, or “Patriot Party,” is written right-to-left on the side of the truck, but left-to-right on the back.

(Thanks to our commenter Peter for suggesting this topic.)

In my last post about bicycle parking, I noted that the enforcers didn’t seem to be making much of an impact on illegal bike parking, except maybe at the margins (I’d be tempted to park there more often if I didn’t have a reliable space at my apt. building).

Another rule in Adachi-ku that’s only effective at the margins is the ban on smoking on the streets. In a reverse of the common American rule, in Japan smokers are often allowed to smoke in designated areas of public buildings but banned from smoking on the street. This makes for some smoky izakaya, but to me it makes sense because Japan’s narrow streets and urban lifestyle mean you are affected more by street smokers than you would be in a big American city.

Unfortunately, the bans tend to be ignored by whoever is insensitive enough to light up. They obviously know it’s against the rules but wear a “screw you” scowl on their faces and no one does anything.

One effort to combat these scowlers has been to enhance enforcement in high-traffic areas by dispatching workers who enforce the rules by collecting small fines on the spot. Adachi-ku has imposed such a ban since October 2006 starting with a 1,000 yen fine in the Kitasenju Station area. Ever since I have been in the area I have seen elderly people (volunteers I presume) asking some very surprised and incredulous smokers to pay 1,000 yen on the spot.

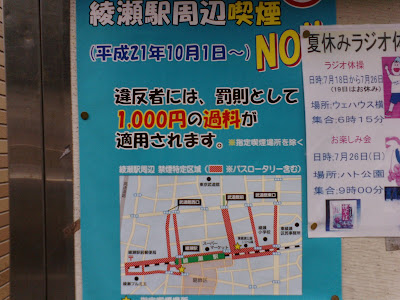

Similar exchanges are expected to come to my neighborhood this October as the fine is set to be expanded to include the Ayase Station area:

|

| From Adachi-ku bicycle parking enforcers |

The details of anti-smoking ordinances vary from place to place, but most appear to follow similar guidelines – ban smoking on the street everywhere (except some small smoking areas) but only enforce in areas of major foot traffic such as train stations. Many places such as Tokyo’s Chiyoda-ku post their enforcement stats online. Since beginning its policy in November 2002, Chiyoda-ku has fined a total of 42,230 people. Though I could not find figures on whether these people are actually paying the fines, if everyone has paid they have collected a total of 84.5 million yen, which adds up to something like 11.3 million yen a year.We also don’t know how many people the enforcers tried to stop but couldn’t.

For its part, Adachi-ku claims to have issued 3,498 fines in the Kitasenju area. As noted above, the preferred collection method is to demand payment on the spot. Enforcers are required to show proper ID upon request, and you are allowed to appeal if you don’t think you deserve the fine. However, there appears to be nothing the enforcers can do if you simply ignore them or refuse to take possession of the ticket.

In the initial period of enforcement, Ayase can probably expect a similar reaction that was documented when Kobe expanded its enforcement in 2007 – refusals by people who claim ignorance of the rule, people tossing out cigarettes just before entering the restricted area, and lots of people simply refusing to acknowledge the existence of the enforcers. Seeing the jerks who light up even when they know the smoke bothers everyone is one of my pet peeves, so here’s hoping our friends the elderly enforcers can get the job done.

Yesterday evening on the way home I caught Adachi-ku’s bicycle parking enforcers in action:

|

| From Adachi-ku bicycle parking enforcers |

The open area outside Ayase Station’s east exit is normally filled with illegally parked bikes (because it basically serves no other function). As in most areas, Adachi-ku bans bike parking near stations except in designated parking lots (there is one that’s free of charge on the south side and several fee-based ones). But in reality, most of the time the only thing stopping people from parking in this area are some old men in yellow vests (apparently officially sanctioned volunteers) who verbally warn people not to park there (even as 5 others are parking their bikes directly behind them).

But about once a week the enforcers come around, and it’s on these days that the park becomes oddly bike-free. On this Saturday in particular I was walking in an area that’s usually so flooded with bikes it’s impossible to walk through comfortably, but when the enforcers came around there were only two or three bikes to be found. Somehow everyone seems to know what day the enforcers will be there.

According to the Adachi-ku homepage, the district only enforces bicycle parking within a 300-meter radius of train stations, as those are the places where offenders concentrate.

If your bicycle is caught by the enforcer’s net outside Ayase Station, you must make your way to the Kita-Ayase relocation center (on foot, presumably). To retrieve a bike that’s been confiscated will cost you 2,000 yen and require you to produce proof that you own the bike along with a working key. Act fast, though – bikes in custody for two months will be “disposed with.” While I don’t know exactly what Adachi-ku does with the orphaned bikes, many abandoned bicycles nationwide end up exported to North Korea, so if you don’t want to fund Kim Jong Il’s regime, you need to retrieve your bike as soon as possible!

A Yomiuri photo of bicycles slated for export.

The Wikipedia article on this issue makes an interesting point – in most cases, there are more people who benefit from illegal bike parking than who are adversely affected by it. No one might be explicitly advocating that bikes should be permitted to park wherever they want, but the fact remains that the fee-based parking lots are expensive and often inconvenient. This means that politicians have a hard time taking decisive action as it would upset the population.

Comments are closed — please join the discussion here.

I’ve written several posts this year regarding the absurdity of the foreign policy of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ). The politicians in the party regularly read off a laundry list of popular positions, with no realistic basis of how these policies would affect Japan’s national interest. This includs the US alliance, Japan’s dispatch of forces overseas, the UN, and relations with Asian neighbors. The cornerstone of this collection of cognitivie dissonance is distancing itself from its primary ally of more than half a century without any alternative security policy — madness, pure and simple.

Here are some examples noted in my previous posts:

We want to move away from U.S. dependency to a more equal alliance… We are only looking for an equal relationship, which we believe the U.S. also prefers.

The DPJ regards the the Japan-US alliance as very important… But we think that Japan should say what it needs to say to the United States. In return, we will be involved at the frontlines in UN activities.

For for all intents and purposes, the DPJ has no foreign policy — only a random collection of popular positions snatched from opinion polls. Yet reality is now catching up to the DPJ as it faces the strong likelihood that it will take power in the election to be held next month. Specifically:

* The party now calls for strengthening the US alliance without conditionals and hesitations previously held in official party policy.

* The DPJ is now silent on its previous opposition to maintain naval ships in the Indian Ocean to refuel US warships used for Afghanistan security.

* Policy concerning the deployment of ships to Somalia remains undecided, but there is no criticism of LDP policy in this regard.

On a sidenote, I also expect there will be a reduced focus on the abstract call that Japan be a more practive “member of Asia.”

Not surprisingly, the DPJ apologist crowd is calling this a welcome move towards realism. I basically agree. But where is this going? More on that as the election date of August 30th approaches.