It was announced on January 28th that the downtown Kyoto location of the Hankyu department store will be closing in autumn. Sales at the store, which opened in 1971, had fallen to a pitiful 1/3 of peak volume, which was reached back in 1991 on the precipice of the bubble. I had originally begun writing a post on the circumstances leading to the closing, the reaction to it, and the possible impact on the area but a planned paragraph on the larger history got out of hand and I ended up with about 2000 words on the history of the department store in Japan in general. Therefore, I have decided to save the discussion of the current events aspect for another post and publish the history piece right now.

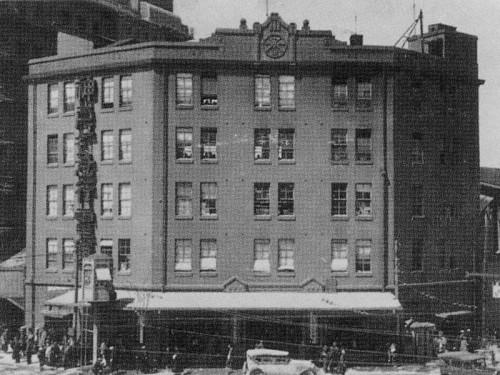

Kyoto’s Hankyu Kawaramachi in the 1970s

The store is located on the SE corner of the bustling Shijo – Kawaramachi intersection, just above the terminal of the Kyoto Line of Hankyu rail that links downtown Kyoto with Osaka’s downtown neighborhood of Umeda. (Trivia time: technically the Kyoto line terminates one stop before Umeda in Juso, with service between those two stations technically running over the quadruple track of the Takarazuka line, but this is an internal technicality and for all practical purposes the lines terminates at Shijo-Kawaramachi one one end, and Umeda on the other.) The presence of Hankyu department store above the Hankyu railway terminal is of course no coincidence, as the confluence of private regional railroads and departments stores is a distinctive and rather unique characteristic of the history of both industries in Japan, which had a profound impact on Japanese urban development in the 20th century. Although the Hankyu department store only opened in 1971 and the terminal beneath it had only opened in 1963, their Kyoto Line had linked Kyoto and Osaka for decades before that, with the section between Saiin (西院) Station and Omiya (大宮) Station (which had been the terminal before the Kawaramachi station opened, and had gone by the name of Kyoto Station) having been the first subway train in all of Kansai. (See timeline here.)

The intersection of Shijo and Kawaramachi street (四条河原町) is the heart of downtown Kyoto, which has long been anchored by large department stores – and in fact Kyoto is itself the birthplace of many of the dry-goods stores known as 呉服店 (gofukuten, roughly “traditional Japanese-style clothing stores” as opposed to 洋服店 (youfukuten) or “Western-style clothing stores”) that eventually evolved into the modern department store goliaths. Even department stores that originated in Edo or Tokyo (same city, different times) had strong ties to Kyoto, which was the center of the Japanese textiles and clothing industry until western style clothing took over as daily fashion in the 20th century.

The intersection of Shijo and Kawaramachi street (四条河原町) is the heart of downtown Kyoto, which has long been anchored by large department stores – and in fact Kyoto is itself the birthplace of many of the dry-goods stores known as 呉服店 (gofukuten, roughly “traditional Japanese-style clothing stores” as opposed to 洋服店 (youfukuten) or “Western-style clothing stores”) that eventually evolved into the modern department store goliaths. Even department stores that originated in Edo or Tokyo (same city, different times) had strong ties to Kyoto, which was the center of the Japanese textiles and clothing industry until western style clothing took over as daily fashion in the 20th century.

Hankyu is not just one example of the peculiar symbiosis between Japanese railways and department stores, but its originator. Unlike all of the other department stores that I will be mentioning later, Hankyu was a train company first, only expanding into the retail business later on. The predecessor to the Hankyu Railway Company was Minou Arima Denki Kidou (箕面有馬電気軌道), or the Minou – Arima Electric Railway, and called Kiyu Densha (箕有電車). (kidou is a now rarely used word that translates to “permanent way” in English, referring to the physical infrastructure of railway tracks.) Starting in 1906, Kiyu Densha first ran trains between Umeda and Ikeda, Ikeda to Takarazuka to Arima, and to Minou. After some rapid expansion through both construction and acquisition, they changed their name to Hanshin Kyuukou Dentetsu (阪神急行電鉄) or Osaka – Kobe Express Railroad, in 1910. In 1943 they merged with Keihan Denki Kidou (Kyoto – Osaka Electric Railway, 京阪電気鉄道) and changed their name once again to Keihanshin Kyuukou Dentetsu, (京阪神急行電鉄), which meant the Kyoto – Osaka – Kobe Express Railway. In 1949 the union came to an end, with the Keihan unit being spun off once again into the present Keihan Electric Railroad, and finally became the Hankyu Corporation in 1973.

Hankyu Umeda Station, ca. back in the day

Hankyu Umeda Station, ca. back in the day

Hankyu’s entrance to the retail market was driven by the company’s founder Kobayashi Ichizo, which naturally has a page of hagiography to him on their corporate site. Although the Hankyu Department Store (阪急百貨店) proper opened in 1929, there were actually two significant stages before that. The first was in 1920, when the Tokyo based Shirokiya (白木屋) rented the first floor of the Hankyu Umeda Station building, sensing the obvious business opportunity of a store directly connected to a major railway terminal. Shirokiya was founded in Tokyo’s Nihonbashi district in 1662, when it was still Edo, and became a modern corporation under the name of Shirokiya Gofukuten in 1919, just before opening their store in Umeda. Shirokiya Umeda sold food and other grocery store items, while Hankyu turned the second floor into a large affordable eatery called the “Hankyu Cafeteria” (阪急食堂). After Shirokiya’s lease ended in 1925 Hankyu booted them out and turned the 2nd and 3rd floor into the “Hankyu Market” (阪急マ-ケット), but it is unclear what exactly replaced Shirokiya. In 1929 this was finally developed into the Hankyu Department store, which is widely recognized as the pioneer of the “railway terminal department store” model that can now be seen throughout Japanese cities. In 1947 the Hankyu Department Store was established as a separate company from the Railway, but they remained under the same holding company, although the names have changed slightly yet again following the recent merger between the Hankyu and Hanshin (Osaka – Kobe) groups. (See this Japanese language site for a great history of the Hankyu Umeda station, including many old photos and maps.)

Significantly, Shirokiya would later became the Tokyu Department Store, as Tokyo’s answer to the Hankyu model of retail and railway symbiosis, after being bought by the Tokyo Railway. Presumably this was related to their experience in developing the market in Umeda. Incidentally, although there is no mention that I can find anywhere on official looking pages, I did find a couple of references online mentioning that Shirokiya had originally been a well-known clothing wholesaler (呉服問屋) in Kyoto before establishing a retail store in Edo, a pattern that is seen repeated more reliably in another example below.

The old Shirokiya store.

The old Shirokiya store.

Just a couple of blocks to the west, along Shijo, one can also find the original Daimaru department store, which like Takashimaya was born in Kyoto, but later moved their headquarters to Osaka. Daimaru was founded in 1717 as the Gofukuten Daimonjiya (呉服店大文字屋), in Kyoto’s Fushimi ward, well south of the current downtown location. In addition to their primary business as a retail establishment they also had a currency exchange counter, which might surprise those who remember that Japan was virtually closed to foreign trade during this period. In fact, exchanged were not being made between foreign money and Japanese money, but between the Japanese gold, silver, and bronze coins, for which a 1-2% service charge was exacted. Daimonjiya (presumably named for Kyoto’s famous landmark / festival) expanded early, to Osaka’s Shinsaibashi in 1726 and Nagoya’s Honmachi in 1728 (later closed), which is when they changed the name to Daimaru. After reorganizing as a modern corporation under the name of Daimaru Gofukuten in 1908, they opened their first modern department store at the current location in Kyoto in 1912. Although this is the location of their first actual department store, the Shinsaibashi site on which they opened in 1726 is their current flagship store, which is doing well enough to have opened a new annex building directly across the street from the original building just last year.

Just a couple of blocks to the west, along Shijo, one can also find the original Daimaru department store, which like Takashimaya was born in Kyoto, but later moved their headquarters to Osaka. Daimaru was founded in 1717 as the Gofukuten Daimonjiya (呉服店大文字屋), in Kyoto’s Fushimi ward, well south of the current downtown location. In addition to their primary business as a retail establishment they also had a currency exchange counter, which might surprise those who remember that Japan was virtually closed to foreign trade during this period. In fact, exchanged were not being made between foreign money and Japanese money, but between the Japanese gold, silver, and bronze coins, for which a 1-2% service charge was exacted. Daimonjiya (presumably named for Kyoto’s famous landmark / festival) expanded early, to Osaka’s Shinsaibashi in 1726 and Nagoya’s Honmachi in 1728 (later closed), which is when they changed the name to Daimaru. After reorganizing as a modern corporation under the name of Daimaru Gofukuten in 1908, they opened their first modern department store at the current location in Kyoto in 1912. Although this is the location of their first actual department store, the Shinsaibashi site on which they opened in 1726 is their current flagship store, which is doing well enough to have opened a new annex building directly across the street from the original building just last year.

Mitsukoshi Gofukuten (From this neat blog on Meiji era Japan.)

Mitsukoshi Gofukuten (From this neat blog on Meiji era Japan.)

Next I would like to mention Mitsukoshi, even though it was not exactly founded in Kyoto and does not currently even have any locations in the city. It is well known that the future Mitsukoshi department store was founded by Mitsui Takatoshi as the Echigoya Gofukuten (越後屋) in Edo (now Tokyo) in 1673, and was the first semi-modern retail clothing store, leading the way for those mentioned above. Like Daimaru, they also had a currency exchange window, which developed into the Mitsui Bank and later formed the basis for the Mitsui Zaibatsu / Group. (Incidentally, the Kyoto Hankyu building is actually owned by Mitsui Sumitomo Real Estate, and leased to Hankyu.) Less well known is the fact that Mitsui was at the same time operating a location in Kyoto, but rather than a retail store like the company in Edo was a purchaser/wholesaler (仕入店), and this Kyoto office was apparently considered the headquarters in the early days of the company. It was first located in the Nishijin (西陣) district, which at that time was the center of Japan’s textiles industry on Muromachi Street in Yakushi-cho (室町通薬師町), but it soon moved to the south, and became the first Echigoya retail store in Kyoto. Although Mitsui later sold most of the land after the store closed, they kept a small portion at the corner of Nijo and Muromachi, which is now a memorial park to the old Kyoto store, which appropriately contains a shrine to Inari, the Shinto fox god of wealth. (See Google map below for location, and photos plus more info in Japanese here.) Although I couldn’t find any reference to it online, I believe I have also seen a photograph of an ornate Meiji era style Mitsukoshi store labeled as having been at the very same Shijo-Kawaramachi corner as Hankyu and Takashimaya, on the northeast corner. I think the photo was from the 1920s or 1930s, and that it said the store burned down, without being rebuilt.

<iframe width=”500″ height=”350″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” marginheight=”0″ marginwidth=”0″ src=”http://maps.google.co.jp/maps?f=q&source=embed&hl=ja&geocode=&q=%E5%AE%A4%E7%94%BA%E9%80%9A+%E5%86%B7%E6%B3%89%E7%94%BA&sll=34.999875,135.720345&sspn=0.007145,0.006888&brcurrent=3,0x6001088730deeea1:0xbb15bb050546e710,0&ie=UTF8&hq=%E5%86%B7%E6%B3%89%E7%94%BA&hnear=%E5%AE%A4%E7%94%BA%E9%80%9A&ll=35.009626,135.751302&spn=0.013302,0.036659&t=h&layer=c&cbll=35.013631,135.75806&panoid=c7c7YpzPnKihu9JVZ1qOeQ&cbp=12,332.33,,0,16.54&output=svembed”></iframe><br /><small><a href=”http://maps.google.co.jp/maps?f=q&source=embed&hl=ja&geocode=&q=%E5%AE%A4%E7%94%BA%E9%80%9A+%E5%86%B7%E6%B3%89%E7%94%BA&sll=34.999875,135.720345&sspn=0.007145,0.006888&brcurrent=3,0x6001088730deeea1:0xbb15bb050546e710,0&ie=UTF8&hq=%E5%86%B7%E6%B3%89%E7%94%BA&hnear=%E5%AE%A4%E7%94%BA%E9%80%9A&ll=35.009626,135.751302&spn=0.013302,0.036659&t=h&layer=c&cbll=35.013631,135.75806&panoid=c7c7YpzPnKihu9JVZ1qOeQ&cbp=12,332.33,,0,16.54″ style=”color:#0000FF;text-align:left”>Click for large map.</a></small>

The last traditional department store that deserves mentioning is the one with the least history in the city, despite being one of the most visible today. I speak of course of JR-West Isetan, located in tower of the Kyoto Station building. WEST JAPAN RAILWAY ISETAN Ltd., as the company is properly called, is 60% owned by JR West and 40% owned by Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd., but was founded in 1990 before the Isetan / Mitsukoshi merger, and so was originally a joint venture of JR West and Isetan. Remember that since privatization JR West is no longer government owned, but publicly traded on various stock markets. Isetan was itself founded Tokyo in 1886 as yet another gofukuten, and like the rest of the big ones evolved into a modern department store in 1930 when they opened their flagship store in Shinjuku. Isetan never had a store in Kyoto until September 11 1997, when the JR West Isetan department store opened along with the brand new Kyoto Station building itself, which had been newly erected to replace the bland concrete building that had been constructed as a temporary station to replace the classic style station building that had been lost to fire in 1950. For whatever reason, JR West did not partner with a department store chain that already had ties to Kyoto (maybe they tried and failed, I really have no idea), but regardless, the idea that a full size department store was an essential anchor to a new, modern station building reinforces the long union between railways and department stores in 20th century Japan, started at Hankyu Umeda 70-odd years earlier.

The last traditional department store that deserves mentioning is the one with the least history in the city, despite being one of the most visible today. I speak of course of JR-West Isetan, located in tower of the Kyoto Station building. WEST JAPAN RAILWAY ISETAN Ltd., as the company is properly called, is 60% owned by JR West and 40% owned by Isetan Mitsukoshi Holdings Ltd., but was founded in 1990 before the Isetan / Mitsukoshi merger, and so was originally a joint venture of JR West and Isetan. Remember that since privatization JR West is no longer government owned, but publicly traded on various stock markets. Isetan was itself founded Tokyo in 1886 as yet another gofukuten, and like the rest of the big ones evolved into a modern department store in 1930 when they opened their flagship store in Shinjuku. Isetan never had a store in Kyoto until September 11 1997, when the JR West Isetan department store opened along with the brand new Kyoto Station building itself, which had been newly erected to replace the bland concrete building that had been constructed as a temporary station to replace the classic style station building that had been lost to fire in 1950. For whatever reason, JR West did not partner with a department store chain that already had ties to Kyoto (maybe they tried and failed, I really have no idea), but regardless, the idea that a full size department store was an essential anchor to a new, modern station building reinforces the long union between railways and department stores in 20th century Japan, started at Hankyu Umeda 70-odd years earlier.