About a week ago the New York Times had an article entitled “Seeking Recognition for a War’s Lost Laborers” on the lack of recognition for the Asian victims of Japanese forced labor in the construction of the famous “Railway of Death.” According to the article, the history of the 200,000-300,000 Asians who were employed, and often killed, in the construction of the railway, which was being constructed to link Bangkok and the Burmese (Myanmarese) capital of Rangoon (Yangon) to provide logistical support for Japan’s invasion of Southeast Asia, has been almost completely overshadowed by stories of the smaller number of Western POWs.

Between 200,000 and 300,000 Asian laborers — no one knows the exact number — were press-ganged by the Japanese and their surrogates to work on the rail line: Tamils, Chinese and Malays from colonial Malaya; Burmans and other ethnic groups from what is now Myanmar; and Javanese from what is now Indonesia.

“It is almost forgotten history,” said Sasidaran Sellappah, a retired plantation manager in Malaysia whose father was among 120 Tamil workers from a rubber estate forced to work on the railway. Only 47 survived.

[…]

By contrast, the travails of the 61,806 British, Australian, Dutch and American prisoners of war who worked on the railway, about 20 percent of whom died from starvation, disease and execution, have been recorded in at least a dozen memoirs, documented in the official histories of the governments involved and romanticized in the fictionalized “Bridge on the River Kwai,” the 1957 Hollywood classic inspired by a similarly named best-selling novel by Pierre Boulle.

One reason given for this inequality of historical memory are that virtually none of the Asian victims were from Thailand, giving the local government little incentive to commemorate them. Another is that, unlike the American and British POWs who wrote memoirs and gave countless interviews to journalists and historians, virtually none of the Asian laborers were literate, and they lacked ready access to mass media.

At this point, I would like to present some photos I took at a very peculiar museum that Adam, his (now) wife Shoko, and I visited when we were in Kanchanaburi, the location of the famous Bridge on the River Kwai.

The Jeath War Museum (JEATH is an acronym for Japan, English, American and THai) is a rather eccentric museum based on the collection of a wealthy Japanese history buff, who apparently purchased a building a number of years ago, stocked it haphazardly with local WW2 memorabilia of both great and small interest, and has not had arranged to have it cleaned since.

First, some photos from outside the museum itself.

This is a picture of the famous Bridge which I quite like.

Here are Adam and Shoko posing with the bridge behind them. I do not know the sleeping man, but I have to assume that he is a war criminal of some kind.

This is a silly little train which lets tourists ride across the bridge and 1 or 2km into the jungle on the other side, and then ride backwards to the other side.

I blurrily snapped this memorial obelisk in the jungle across the river, from aforementioned silly train. It says something along the lines of “the remains of the Chinese army ascend into heaven.”

This plaque is location near the bridge. I did not, however, see one for the British POWs, although I certainly could have just missed it.

And now we reach the museum portion of our tour. I do not seem to have any photographs of the entrance area, but the first thing you see upon approaching the entrance to the museum proper are these statues of historical figures, with biography written on the wall behind them. I will transcribe the highly amusing text another time.

Here is Tojo.

Adam and Shoko again, with their good friends Josef Stalin and General Douglas MacArthur.

The lovable Albert Einstein gets a wall as well.

Inside the museum we are confronted with more dramatic statues, such as this tableau of POWs constructing the railway.

Here is one in a cage. Note the real straw.

Eerie closeup of another caged POW statue’s face.

Adam and his new friend, the WW2-era Japanese soldier driving an old car.

The driver.

Another old car. I do not recognize the make, but it is covered in dust that may weigh as much as the steel.

US Army signal core teletypewriter

Recreation of Japanese army tent

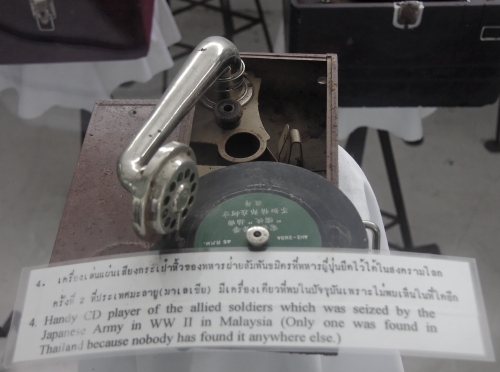

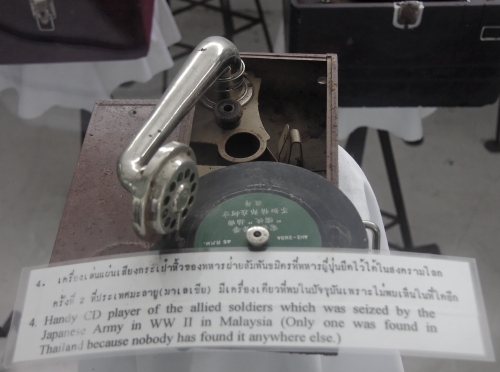

Read the text carefully. Do you know when the CD was invented?

A message from Japan to the Thai people. It’s a bit hard to read, so if anyone wants I can transcribe it.

A British anti-Japan political cartoon

Overall, the museum is a complete shambles. While it has a huge array of cool stuff, it is strewn about almost at random, covered in dust, and sometimes behind other stuff. Not to mention placed in crowded and un-lit cases with poor labeling. Despite the numerous flaws, it is certainly worth a visit if you are in the area, but I can’t say that it will do much to provide any sort of historical narrative, and certainly does not even try to meet the standard hoped for by the Times article I began this post with.