[Note, this article as posted had been screwed up by a couple of misplaced cut/paste operations, and I believe has now been fixed.]

Currently caught up in a fit of techno lust over Canon’s recently announced

EOS 400D/Rebel XTi/Kiss X and feverish speculation over what they may be announcing next I’ve been spending quite a lot of time reading article and forums about their latest camera technology.

In the results of a routine Google search for “Canon history” I stumbled across this forum post on the very active photogrpahy discussion website photo.net, which in responding to a link to Canon’s own camera museum website says that he “was very interested in the brief reference to the involvement in Canon development by the American consultant, William R. Gorham, who became a naturalized Japanese citizen shortly before WWII.”

Mr. Gorman is mentioned only in a sidebar of the company history section, entitled “Valuable Suggestions Received from an Individual Outside the Company.”

There was an unusual American engineer whose name was William R. Gorham. He became a naturalized citizen of Japan in l941, and made strong contributions to the establishment of Nissan Motor Company. He had his Japanese name as Katsundo Gorham, and visited Canon often during the 1940s to provide valuable suggestions and recommendations regarding the procurement of machinery and technological innovation. He proposed and implemented the concept of “Scheduled Daily Production,” in which the daily target of the production was predetermined to achieve the uniform flow of camera production. Gorham also suggested a system in which the product inspection department becomes independent of the plant manager and is placed directly under the president. In this manner, the inspection could be performed without regard to the whims of the plant manager. In addition to the introduction of the rational improvement plan, which was somewhat akin to the American method, Gorham made a tremendous contribution to the modernization of Canon through his warm and energetic personality. When Gorham passed away in October 1949, at his bedside was none other than Takeshi Mitarai.

Takeshi Mitarai was the president of Canon from 1942, and longtime friend of Saboru Uchida, co-founder of the company formed to produce the “Kwanon” Camera, which was later renamed Canon-a brand which eventually became the name of the company itself.

Amazingly, this single paragraph is virtually the only information online in English about Mr. Gorham, with scarcely more avaliable in Japanese. This one mention though is intriguing enough, with my strong interests in both history and photography, to inspire me to gather all of that information.

Probably the single best source I found is a small press / vanity press English language translation of a biography said to have been written by his colleagues following his death in 1949. Interestingly, the translator is his son Don Cyril Gorham. We will return to Cyril later on. Luckily, Lulu.com offers this book both in a $12.99 paper version and a digital download, refreshingly priced at a mere $4.41. Or perhaps I should say, potentially the best source. For the moment, I have only bookmarked this page. I will buy the download later on tonight, but only after I have finished this exercise in purely online research. While one might be able to make a case that this digital download counts, I believe that a file which a: required payment and b: is not indexed by search engines does not count.

William R. Gorham ca. 1918, courtesy of Nissan

I also did a search for William R. Gorham in Amazon’s search inside a book feature, and found only a handful of mentions worth noting (Amazon does not seem to carry the biography, for some reason). No book seems to mention him more than once, or give any more information than the following three.

The first is from Making and Selling Cars: Innovation and Change in the U.S. Automotive Industry by James M. Rubenstein, which on page 339 says “Nissan was founded in Yokohama in 1933 by an entrepreneur, Yoshisuke Ayukawa, with engineering provided by an American expatriate, William R. Gorham.” This is the only mention in the book.

The other book which mentions Mr. Gorham is Datsun 280, Nissan 300 Zx, a coffee table format book for fans of this discontinued automobile written by Brian Long. Like the Rubenstein book, it mentions Gorham just once, in this brief passage which begins at the bottom of page 9 and continues onto page 10, in a section on the history of automobiles in Japan.

In 1925, Kaishinsha had changed its name to the DAT Jidosha Seizo Ltd (the DAT Motor Car Manufacturing Co. Ltd) following a merger with the Jitsuyo Jidosha Seizo. This firm had been founded in 1919 to build three-wheelers designed by the American engineer William R. Gorham, who later helped with the design of the Mitsubishi Zero fighter aircraft. Although the three-wheelers were unsuccessful financialy, they did provide the basis for the four-wheeled Lila light car of 1921. Many were used as taxis in Japan, and the continued to be made for several years after the DAT merger.

The third is Japanese Industry in the American South, by Choong Kim, which on page 7 says:

And if the Japanese had been too ingrown to learn from William R. Gorham, the American electrical engineer who is considered the founder of the Datsun (Nissan) motor company in terms of technology, Nissan might not be the success we see today.

The same Google search also provided me with the Japanese edition of the same Canon history page, which gave me Gorhman’s Japanese name, 合波武克人(ごうはむ・かつんど) pronounced Gohamu Katsundo, that he had taken upon naturalization as a Japanese citizen. I then searched for his Japanese name on Japanese Google. There were exactly three results. The first was the same Canon history page from which I had learned his Japanese name in the first place.

Gorham automotive tricycle, 1920, courtesy of Nissan

Next was this page on Nissan’s pre-war history, which credits Gorham as one of the two fathers of the company for his invention of the “Gorhman automotive tricycle,” (picture above from Nissan) which combined a harley engine with a rickshaw to produce a primitive automotive vehicle that could be affordably produced in an as-yet industrially underdeveloped nation. Gorham’s design, which should strike a cord with anyone familiar with more primitive automotive vehicles such as Thailand’s tuk-tuk or the Phillipino jeepney currently being manufactered in some less developed yet partially industrialized economies, and which became the basis for the first 4-wheeler produced by Jitsuyo Jidosha Co., Ltd, one of the three companies that formed the modern Nissan company.

Last of all was a really special find- a photograph of Gorham’s grave with two-paragraph biography on the homepage of the Tamarei’en cemetary in Tokyo (described on Wikipedia as the first public cemetary in Japan), where he is buried. The cemetary web page has similar info on many dozens of notable figures interned there (note: in Japan, cemetaries are usually Buddhist style, only containing the cremated ashes of the deceased within or under a memorial), including several other foreigners, such as the man who introduced Indian curry to Japan or a Russian who fled to Japan due to the revolution, lost his citizenship, and became a pro-baseball player for the Giants when the players were increasingly called away for military service in the 1930’s.

Anyway, here is my translation of the mini-bio from the cemetary website.

William, R. Gorham

William, R. Gorham

Lived 1888 (Meiji 21) to October 24, 1949 (Showa 24)

A machine technician of the Taisho and Show periods

Burial location: Ku 24 Shu 1 Soku 11

Born near San Francisco, in the United States of America. Came to Japan in 1918 (Taisho 7) to introduce and use his technology, with the goal of developing air mail systems and establishing an aeroplane manufacturing company. He designed and introduced Engines, airplanes, automobiles, telephone switches and fast turret lathes. He also imported single engine biplanes and sold them to the Japanese military. In later years he became a consultant for Canon and assisted them by developing a more efficient production system. He also worked as a consultant for Kokusan Seiki (Later became Hitachi Seido Co., Ltd.) and was also involved in designing machine tools. In the early 1940’s the international situation began growing tense, and the Japanese government started deporting foreigners. After painful consideration, Gorham became a naturalized Japanese citizen on May 26, 1941. He took the Japanese name of Gouhamu Katsudo (合波武克人).

His son, Don C. Gorham, graduated from Tokyo Imperial University in March of 1941, and although he wanted to continue his study of Japanese literature in graduate school, in accordance with his parents wishes he instead returned to the America, received his Doctoral degree in literature, and found a job related to the improvement of Japanese/American relations. Thinking of the circumstances of the antipathy towards gaijin at the time and the Tokko [Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu; Special Higher Police, Japan’s equivalent to the Gestapo], one can understand how heroic Gorham’s decision was, and how much he must have loved Japan. Postwar Gorham became an employee at Nissan Automobiles and challenged himself in the industrial field. He worked not just for the sake of his own company, but became a key figure in the rebirth of Japan’s industrialization and economic development, and was a forerunner to the later high growth period. He died a premature death due to illness in 1949. Grand Prix press’s, “The legend of William Gorham: the American Engineer who became Japanese”and others have appeared.

When I read this I was happy to see that it confirmed my strong suspicion that the translator of the biography on Lulu.com was in fact William Gorham’s son. There was, however, one thing I had overlooked. On the biography page there is actually a link to view the back cover of the book, which would have told me this fact earlier. Since the low-res jpeg is very hard on the eyes, I will transcribe it here.

Don Cyril Gorham, the translator, is the younger son of William R. and Hazel H. Gorham. Born in California, but taken as an infant to Japan an 1918, Don Gorham is fluent in Japanese, having spent his entire pre-war education in Japan–from nursery school through graduation from Tokyo Imperial University in March of 1941, with a degree in Japanese language and literature. Shortly after graduation, he returned alone to the United States, where he was commissioned into the U.S. Naval Reserve and served on active duty for the next six years, followed by further U.S. civil service work. In 1972, he retired from the U.S. government and began his career as a freelance interpreter/translator. He has served as interpeter for senior U.S. and Japanese government officials, including two U.S. presidents, several U.S. Cabinet members, as well as several Japanese Prime Minsters and Japanese Diet members.

In addition, Don Gorham is a graduate of the Naval War College and has been a member of the American Translators Association (ATA) for over 30 years. In 2000 the ATA made him an honoraary member, an award reserved for individuals who have distinguished themselves in the translation/interpresting profession. At present, the ATA has only seven living honorary members.

Don Gorham has three grown children and lives with his wife of 61 years in Silver Spring, Maryland.

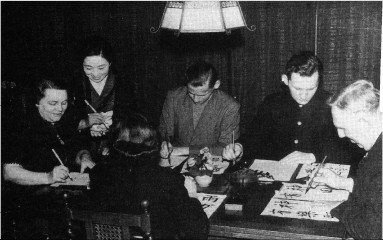

While it does not directly tell us anything new about his father, this back-cover authors biography of William’s son Don Cyril was interesting, and I figured I should also try running a search on Don Cyrcil to see what else I could turn up. What I found was this article at the ATA Japanese Language Division newsletter from Spring 2000, announcing his selection as an honorary member, as referred to on the book cover. The article does not have much new in the way of information, but does have this picture, captioned “Gorham (in university student uniform) practices shodo with family and friends in Tokyo.”

So now that I have found probably almost all I can about this man’s live using only Google searches, let’s say that I was going to prepare a genuine biography of William R. Gorham. Where could I look, what sort of resources could I turn to?

Even though the information collected so far is somewhat sketchy, it does give us several good leads. The most obvious place to start would be with his son, who at least as of 2005 was still living in Maryland. Since Don Cyril Gorhman cared enough about the story and life’s work of his father to translate and arrange some form of publication for the biography that had been written by his father’s colleagues after his demise, I think it is probably a good bet that he would be forthcoming with documents and information about his father.

Probably the the next most fruitful place to turn would be the companies in Japan that honor him in their official company histories: Canon and Nissan. If both companies care about their own history enough to keep an official timeline on their website, then there must be someone in the company whose job includes supervision of the archives, and they would probably be willing to help dig up the needed information. These certainly were not the only companies with which Gorham was involved, and if others are discovered they would also be worth investigating as well, but he seemed to have had more impact on the early development of Canon and Nissan than any other to which he contributed.

Next might be government records. Certainly there are record of his naturalization-a very rare event in that period, and probably not too difficult to track-and his death (we even know exactly where his grave is), and upon finding his place of residence it may be possible to find other documents, such as his koseki, juminhyo, not to mention all of the US government documents, birth certificate and so on, that may exist in dusty filing cabinets in some basement or geneaological databank.

We could search for correspondence beyond what his son possesses. Although none of Gorhman’s contemporaries are likely living today, their own children or grand-children, probably are, and may have preserved their personal effects as well. Calling upon the descendants of, let’s say, Canon’s Takeshi Mitarai might uncover some more information.

Of course, the existing English biography must contain a wealth of information itself, although as a book written by his own friends is probably more of a third-party memoire than a scholarly biography. I will purchase and download the PDF shortly after completing this post, since having access to it would have ruined my Google only experiment. The ATA newsletter article on the honorary induction of Don Cyril also tells us that their was a biography of William R. Gorham reviewed a few issues ago, by the name of 日本人になったアメリカ人技師、桂木洋二著(The American Engineer Who Became Japanese, by Yohji Katsuragi). This may or may not be the same one translated by his son, but either way a Google search for the author’s name produced no useful results. Perhaps one of the many rare book dealers in Kyoto would be able to locate it.

This experiment, of choosing an interesting seeming but obscure figure and attempting to research as much as possible about that person, is really an exploration of the limits of what information is readily avaliable online. While I was lucky enough to find something as unexpected as the photograph and exact location of his grave, and a number of general facts about his life, the overall picture remains very sketchy. There was no biography longer than a couple of hundred words, no quotes from him or about him, only a single photograph of the vehicle he designed for Nissan’s predecessor, no clear details on the contents of his work for Canon, etc. The important thing, however, is that there was just enough information to suggest the several possible avenues for research, and even these modest results would probably have been considered an almost unfathomable resource by historical researchers before the age of Internet searching.

Readdressing an age-old question: how does a visibly non-Japanese person deal with living in Japan?

Readdressing an age-old question: how does a visibly non-Japanese person deal with living in Japan? He explains that the keys to his huge success were: a) His years of teaching produced a large contingent of people of voting age who knew him from being his student; and b) Dissenting voters appreciated his promises to bring a more open style of politics to the city. In

He explains that the keys to his huge success were: a) His years of teaching produced a large contingent of people of voting age who knew him from being his student; and b) Dissenting voters appreciated his promises to bring a more open style of politics to the city. In  Bianchi’s political style stands in stark juxtaposition with that of a better-known Western-born activist in Japan,

Bianchi’s political style stands in stark juxtaposition with that of a better-known Western-born activist in Japan,  With the Japanese people in an uproar over leaks of personal information, often to unscrupulous scam artists, it should come as nothing less than a slap in the face that the government is publishing their fellow citizens’ home addresses. I’m just a curious nerd, but what’s to stop some right wing group from harassing new citizens for tainting Japan’s supposedly sacred and pure bloodline? (Of course, they’d have to go looking for it at a relatively obscure and boring government website, but gosh darnit, it’s just like that

With the Japanese people in an uproar over leaks of personal information, often to unscrupulous scam artists, it should come as nothing less than a slap in the face that the government is publishing their fellow citizens’ home addresses. I’m just a curious nerd, but what’s to stop some right wing group from harassing new citizens for tainting Japan’s supposedly sacred and pure bloodline? (Of course, they’d have to go looking for it at a relatively obscure and boring government website, but gosh darnit, it’s just like that