Some headline-writing editor is way too excited about those Nye rumors.

Category: Products

Pizza by the slice coming back to Japan!

Though they did not announce exactly when the first store would open, their plans are to open 18 shops in rapid succession in their first year of business. That’s a thankful departure from the Cold Stone Creamery and Krispy Kreme Donuts strategies of pumping up excessive demand for a tiny amount of shops in an effort to generate buzz. So rather than the painfully annoying KK lines in Shinjuku and Yurakucho, here is hoping the Sbarro chains will be as accessible as they are back home.

|

Chocolate low-malt beer makes me sad

As a beer drinker (though I am really liking wine these days), this announcement was truly shocking:

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again — what a sad state of affairs! If I saw this at the store I might be forced to buy it for the novelty value, but apparently it’s only being offered online. Oh well.

This new chocolate low-malt beer (happoshu in Japanese) makes me sad, mostly because of the implications of the company’s decision to make chocolate happoshu instead of chocolate real beer.

What started as a clever way to get around a tax hike in 1994 has today resulted in low-malt happoshu and no-malt “third beer” gaining recognition among the Japanese public as cheaper, viable alternatives to the real thing. In my own life, it is typical to see housewives at the local Ito Yokado buying dinner with a cheaper beer alternative, either for the husband or to drink together (I do a lot of the grocery shopping). How did things come to this?

According to the National Tax Agency, beer has long been Japan’s drink of choice. As far back as 1970, twice as much beer was consumed as Japanese sake. But for a long time, Japan has had a 40% tax on beer sales, higher than other advanced nations (UPDATE: in 2006 it was lowered slightly but remains high). This was never a problem when Japan’s economy was growing, but a tax change in the post-bubble year 1994 triggered events that would transform the local convenience store beer cooler:

Japan’s alcohol tax system divides beer-like malt beverages into four categories based on malt content: 67% or higher, 50 to 67%, 25 to 50%, and less than 25%. An alcoholic beverage based on malt is classified as beer if the weight of malt extract exceeds 67% of the fermentable ingredients. Since Suntory‘s introduction in 1994 of Hop’s Draft, containing 65% malt, a market has emerged for low-malt, and recently, non-malt beer substitutes.

With alcohol tax revenues decreasing as a result of happoshu’s popularity, the Japanese government eventually raised the nation’s tax on low malt beers. In 1996, the tax for products containing 50 to 67% malt was raised to that of beer. Brewers followed suit by lowering the malt content of their products. Today, most happoshu contains less than 25% malt, putting it in the lowest tax category of low-malt beer. In recent years, Japanese brewers have released dozens of brands in attempt to increase their market share. Many of these are marketed as more healthy products, with reduced carbohydrates and purines. Another trend is to use unmalted barley, such as in Sapporo’s Mugi 100% Nama-shibori.

Beer-flavored beverages collectively dubbed “the third beer“(第三のビール, dai-san no bīru) by the mass media have been developed to compete with happoshu. These alcoholic products fall under categories not yet as highly taxed. The third beer beverages either use malt alternatives, or they are a mix of happoshu and another type of alcohol. When comparing 350 ml cans, the third beer brands can be 10 to 25 yen cheaper than happoshu.

Effect on total consumption

These new, less tasty types of beer have grown in importance over the years. Third beer sales overtook happoshu for the first time in 2008, amid a record bad sales year for the beer and beer equivalent industry as a whole. Together, happoshu and third beer sold almost 90% as many cases as real beer (226 million vs. 256 million). In a matter of years, Japan may be drinking more loophole beer than the real thing. The bad sales were attributed to to price hikes (due to high commodity prices in the first half of 2008) and a general shift among consumers away from beer to other options or no drinking at all (due to being too old or a part of the supposedly vice-free younger generation).

Over a longer term, consumption of beer peaked in 1994 at 7 million kiloliters and fell 53% by 2006. The combined beer + happoshu + “other alcohol” numbers went from 7.09 million kL in 1994 to 5.9 million in 2006, a dip of around 18%. from the peak.

However, according to the tax authorities, overall alcohol consumption peaked in 1996 and fell 9.2% by 2006. It is clear that the decline of beer etc. was the biggest drag on the total, as no segment of the industry stepped up to take beer’s place. Beer’s share of total alcohol consumption declined from 73% in 1994 to just 66% in 2006. While shochu and liqueur (mostly chuhai aka shochu “alcopop”) and wine grew over that period (and sake, whisky, and brandy actually declined significantly), there is still nothing approaching beer.

Effects on drinking behavior, conclusion

The rise of happoshu came amid a major recession for the Japanese economy and the first instance of deflation for a developed economy in the postwar era. Just as the 1990s saw the rise of 100 yen stores and Uniqlo discount apparel, these near-beers are the product of downward price pressure and a relative impoverization of a wide swath of Japanese consumers.

This dual taxation appears to have created a similar dual structure in how people drink their beer. According to What Japan Thinks, while around three quarters of those surveyed drink at home, the overwhelming drink of choice was Happoshu: “over one in six of the total population drink happoshu almost every day!” So while a minority will drink beer or other alcohol, it’s clear that my observations of housewives at Ito Yokado aren’t just coincidence — as far as I can tell, the justification for drinking happoshu is that it’s cheap and tastes just good enough to be had with dinner.

The existence of these choices isn’t by itself a bad thing. I am not aware of the tax scheme in the US, but liquor stores are filled with nasty alternatives to good beer (some happoshu brands are much better than Schlitz, just to name one example). The only thing that angers me is that the tax policy has pushed the beer companies to pursue a decidedly low-quality product line in order to avoid their tax bills, to the point that it dominates their marketing such that even their novelty products are happoshu. Could it have been possible to negotiate an overall lower tax on beer that would maximize both quality and tax revenue?

Ultimately, the tax wars over beer ended up hurting everyone involved, concludes a helpful summer 2008 report by Shigeki Morinobu, a former tax regulator who was personally involved in the process between 1993-97. Annual tax revenues from beer and derivatives fell from more than 1.6 trillion yen in 1994 to 1.1 trillion yen in 2007, an enormous drop of 32%. The beer market has shrunk significantly, as detailed above.

Morinobu, in translation and with my full-throttled agreement:

And what about the consumers? The tax debate resulted in low-malt beers overflowing the store shelves. The flavor of beer-type drinks grew worse and worse, which constitutes perhaps the biggest factor behind the trend away from beer drinking, especially prominent among young people. Seen this way, it is clear there are no winners in this war over beer taxation.

In Germany, anything with less than 100% malt cannot be considered beer. Japan, too, should return to the root of the problem and recognize that creating good beer will increase beer’s overall consumption volume and in the end boost national tax revenues. This summer, I prefer to drink 100% malt, real beer.

An uncannily accurate prediction

I just finished reading the book Sketches From Formosa, a memoir by the English Presbytarian missionary Rev. W. Campbell, D.D., F.R.G.S., Member of the Japan Society in 1915. This is one of many wonderful facsimile reprint editions of old books concerning Taiwanese history (in both English and Japanese) published by the Taiwanese historical publisher Southern Materials (南天), which I picked up in their Taipei store. Towards the end of the book he gives his impressions of the Japanese takeover of Taiwan and their policies, and in that section (p. 325-6) was the following passage concerning Japanese efforts to eliminate opium use in Taiwan:

Those who favoured the gradual method of extinction felt that there were serious objections to an immediate adoption of the root-and-branch way of going to work. For example, they said-as many Medical Missionaries have also affirmed-that the latter course would entail unspeakable misery on the opium-smokers themselves, and that the enactment of stringent laws in such circumstances would necessitate a fleet of armed cruisers round the Island to prevent smuggling, with Police establishments and Prison accomodation on a scale which simply could not be hoped for.

Doesn’t this sound like a pretty good description of our current failed drug war policies, from a 1915 perspective?

Switching to eMobile for handheld broadband in the ‘burbs

UPDATE: I ditched eMobile after about a year; this post explains why.

So I switched my mobile phone service to eMobile. This was really part of a much bigger jump over the weekend: I moved from a tiny furnished apartment in central Tokyo to a larger and very Japanese-style apartment on the edge of the metropolis. So far, I can’t say it’s been a bad change. There’s plenty of sunlight out the window, a proper bathroom (unit baths suck!) and enough room to accommodate my [laughable] writing, studying and musical efforts.

One problem I had to solve was staying connected to the outside world. All I wanted was an internet connection: I don’t need a home phone (Skype has me covered there) and I don’t need TV. My building isn’t wired for DSL, so the cheapness of broadband would be outweighed by the cost and hassle of installation.

After some head-scratching, I recalled that eMobile’s basic data plan offers unlimited use of mobile broadband at slow DSL speeds for about 5,000 yen a month. Then I realized that I could get one of their phones and plug it into my laptop’s USB port for unlimited internet access at slower-than-DSL speeds for about 7,500 yen a month, about the same as my average DoCoMo bill (basic plan plus “pake-hodai” and a couple of network services). So I went with eMobile’s basic “smart phone,” the S11HT “eMonster.” I bought it on Friday and have been using it constantly since then.

I am quite pleased so far. I wanted to get a phone with a keyboard for a while. I eyed Softbank’s offerings with interest last year, but was put off by advice from several people that the software sucked (I even heard this from a Softbank sales lady in Roppongi). A friend of mine then bought Softbank’s “Internet Machine,” which is packed with features (including television and GSM roaming) but costs more than my laptop did and, like most Japanese phones, has a unique operating system. Overall, the eMonster does a good job of balancing the sort of things that a fast-paced international digital individual (like yours truly) really needs in life.

The upsides:

- Internet is very fast, both on the handset and on a connected PC. I’m not sure whether I’m actually getting the full 3.7 mbps on this thing, but it sure feels responsive; faster, at least, than the heavily firewalled LAN connection at work.

- Can access any email account with a POP or IMAP server. I now get my Gmail messages straight to my phone. There is also third-party software which allows syncing with Google Calendar (which I also sync to my Outlook calendar at work) and Remember the Milk, meaning that I can have the same calendar and task list on my home computer, work computer and phone. Awesome.

- There are multiple input methods. In addition to the slide-out keyboard, there is a Palm Pilot/Pocket PC-style touchscreen with stylus (which you can use to handwrite characters or tap an on-screen keyboard), a Blackberry-style clicking scroll wheel in the corner, and a directional pad at the base of the phone. Although this encourages a lot of fiddling to find the easiest way to accomplish any given task, it also makes it easy to find a control method that “feels right.”

- Media integration is quite straightforward; just drag and drop folders of mp3s from the hard drive to the device, then Windows Media will pick up the files on a simple directory scan and catalog them appropriately.

- There is a lot of third party software available for Windows Mobile, like Pocket Dictionary and Pocket Mille Bornes (I hadn’t played that game since I was eleven, and I had forgotten how good it is). No more paying monthly fees or signing up to newsletters just to play downloaded games (as DoCoMo generally requires).

- I can run Skype on my phone to call people overseas for next to nothing, although so far I can’t get it to work through the phone’s earpiece–only through speaker or headset.

The downsides:

- eMobile’s network is not as strong as any of the big three providers. In Tokyo, the main place you notice this is on the subway and in basements, as there is never any signal underground (although you can get a good signal above ground anywhere in the 23 wards).

- No RFID chip for mobile payments. I was quite fond of the Suica chip in my DoCoMo phone, as I could charge it with my credit card and roam the city at will. Now I’m back to using a Pasmo card which I have to recharge with cash–bummer.

- The GPS seems more erratic than my Docomo phone’s. Usually it’s off by several blocks.

- Battery life isn’t great when the phone is on 3G and syncing data all day. It’s just about enough: I charged the phone overnight on Sunday and was down to my last bar of battery when I got home from work on Monday. If you plan on spending the night in an atypical location, you’ll need to bring a charger with you.

- Contact management is really complicated in comparison to most mobiles, since Windows Mobile uses a slightly simplified version of Outlook.

- No international roaming. Not a huge deal for me, since my DoCoMo phone could only roam in Europe and certain developed countries in Asia. The WiFi feature largely makes up for this anyway, especially since my family’s house in South Carolina has a good DSL connection and wireless router.

More on plastic bags

Following up on my post about three weeks ago on the movement to curb plastic bag use, the NYT has an article focusing on the success of the Irish campaign.

In 2002, Ireland passed a tax on plastic bags; customers who want them must now pay 33 cents per bag at the register. There was an advertising awareness campaign. And then something happened that was bigger than the sum of these parts.

Within weeks, plastic bag use dropped 94 percent. Within a year, nearly everyone had bought reusable cloth bags, keeping them in offices and in the backs of cars. Plastic bags were not outlawed, but carrying them became socially unacceptable — on a par with wearing a fur coat or not cleaning up after one’s dog.

I think that imposing such fees, essentially a pollution tax being paid in direct response to the pollution itself, may be effective as a means to use market forces for environmental protection. While some libertarian hardliners claim that the only market which matters is the so-called “free market,” operating with no governmental interference whatsoever, in a completely unregulated market the costs of pollution and environmental damage are simply externalized, and born far away from either the producer or consumer of the offending product. By raising the cost of a polluting product, such as a plastic bag, consumers are not just made intellectually aware of the abstract cost which consumption of such a product imposes on the system as a whole, but are forced to make a choice whether or not they, as the responsible party, actually wish to pay the real cost.

Could this be a model for the larger market? It is essentially the same philosophy behind the proposed carbon emissions tax, in which industrial emitters of carbon dioxide are charged fees to encourage thrift and conservation, to reduce the production of greenhouse gases.

On a side note, the article said two more things of which I was not aware. First:

Whole Foods Market announced in January that its stores would no longer offer disposable plastic bags, using recycled paper or cloth instead, and many chains are starting to charge customers for plastic bags.

A positive development from a major US supermarket, and one whose up-scale yuppie customer base will doubtless embrace. Unfortunately, there is still no sign of a nationwide -or even statewide effort, but perhaps competitor supermarkets will be spurred by Whole Foods.

And on a related, yet surprising note:

While paper bags, which degrade, are in some ways better for the environment, studies suggest that more greenhouse gases are released in their manufacture and transportation than in the production of plastic bags.

Rather unfortunate news, I would say. I hope that recycled paper bags, such as the ones which Whole Foods uses, are in fact less polluting. Still, even if paper bags may pollute the air slightly more than plastic, they certainly don’t have as much impact on the sea.

I still think they taste like cardboard

Everyone reading this is familiar with the tasteless paper-filled, paper-textured fortune cookie right? Long thought to have originated as a gimmick desert in one of California’s Chinatowns sometimes in the late 19th or early 20th century, new research strongly suggests that, despite being popularized by the Chinese, fortune cookies were actually invented by Japanese immigrants, who had gotten their inspiration from snacks sold at a Kyoto bakery. The New York Times has an excellent article detailing the whole story, which I must say I find surprisingly convincing. I think anyone else familiar with the wide range of tasteless Japanese traditional snacks (八ッ橋 anyone ? ), the Japanese love for fortunes, and of the tasteless fortune-filled “fortune cookies” distributed inevitably in American Chinese restaurants will also, upon reflection, find the resemblance highly suggestive.

Video: ZEEBRA in the Snickers dimension

I just saw ZEEBRA’s new single “Shining Like a Diamond” on MTV and had to share it. In part of what seems to be a trend of blatant advertising in music videos (which are themselves supposed to be advertisements for a single … my head is spinning).

The narrative: May J fellates a Snickers bar to lure Japanese rapper Zeebra into what I call the “Snickers dimension”, which consists of a multi-racial harem and mountains of Snickers bars. I don’t know how the women keep so trim with nothing but Snickers to eat. Just watch:

Obviously, the other product pushed in the song is diamonds (though Bacardi gets a token mention), which I have seen quite often in Japanese music videos lately. Quite unlikely to be coincidence (just as the sudden Japanese “acceptance” of depression is less a sign of social progress as it is of pharm. companies looking to turn a profit).

One distinction I want to draw – the flashy consumerism that US rappers tout in their songs is more fixated on high-end items like expensive jewelry, Bentleys, and other rewards for making it big against all odds. While there are examples of very crude product placement (Nelly’s “Air Force Ones” comes to mind) in general there’s a process to either (a) select products that are a natural part of the lifestyle (pouring Cristal on strippers fits right in, for example); or (b) at least make the argument that they belong there when there’s some discrepancy (“gangsters don’t dance they… lean back” in promoting the “two-step” dance or 50 Cent bragging about his investment prowess in a line about how Coca Cola purchased his energy drink startup).

This video is totally gratuitous in its pushing of Snickers – the song has nothing to do with it and there’s nothing really indicating how Snickers gained the magic power to transport people to magic multi-racial orgyland. Of course, it’s kind of missing the point to expect US-style product sensibilities from 36-year-old Zeebra. The single father of two is a salaried member of SOLOMON I&I PRODUCTION and as a result could never dream of US-style sky-high record deals, and I’m willing to bet 120 yen (the going rate for a candy bar in Tokyo) that he doesn’t see much in the way of extra cash from the Snickers deal. It sure wasn’t his idea in the first place.

Anyway the sheer artlessness of it all made me laugh my ass off as I finished up the dishes tonight.

A Bathing Shoko

A few days ago I spotted the following sticker just outside Tokyo’s Roppongi Hills:

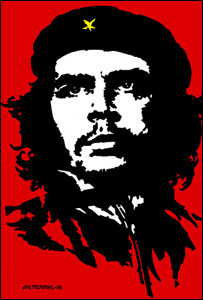

It’s an ironic tribute to former Aum Supreme Truth Cult leader* Shoko Asahara that combines his ugly mug with the iconic BAPE clothing logo (see below). I absolutely loved the image for my own reasons (I am a BAPE fan and an avid consumer of Aum-related developments), but it has taken on new relevance now that the BBC informs me that this year marks the 40th anniversary of Che Guevara’s death. The article discusses the enduring popularity of that one image of him glancing out somewhere with the utmost intensity:

Combined with the mystique and allure of Che and the spirit of revolution, another key to the spread of the image was the complete and intentional lack of intellectual property management on the part of the original photographer and designer, and it has certainly been effective for better or worse. Anyone with a pair of eyes who has visited US college campuses will know how pervasive this image is. And more importantly, the BBC article notes that in Latin America he remains an inspiration for his life and what he stood for, rather than just being a part of the trustafarian poster collection.

However, in Japan the story is a little different. A far more recognizable but similar image is the logo for hip clothing brand A Bathing Ape (aka BAPE) which derives its flagship logo from a combination of the Che image with the Planet of the Apes movies (stunning in their own right). While Che’s logo may stand for the combination of “capitalism and commerce, religion and revolution,” notwithstanding some recent dilution of the brand BAPE’s message is more along the lines of “wear this if you are young and listen to Cornelius”:

I should point out, however, that BAPE has none of the revolutionary hype nor is it even close to the level of pervasiveness of the Che image. It is just a hip clothing brand with a slightly creepy but somehow irresistible logo.

(*Asahara is apparently still revered in one sect of former Aum followers according to recent reports. He will be headed for the gallows for orchestrating the deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subways whenever the Justice Minister gets around to it.)

Attempting to explain just what it is about Louis Vuitton and Japan

One of my favorite blogs at the moment is Marginal Revolution, which is run by a couple of academic economists who basically try to squeeze their science into every facet of life (á la Freakonomics).

A recent post is totally on point with what we talk about here at MFT: namely, Japan’s statistically insane obsession with luxury goods. What’s great about this post is not the post itself, but the wide variety of comments it generated from armchair analysts who all think they know why Japan loves expensive stuff so much.

Some of my favorite theories:

- “Being in a warring society since 12th centuries until before their Meiji restoration, the craftsmanship and other manufacturing skills were cultivated by warlords in order to empower their army.”

- “It might be a substitute for not being able to purchase land.”

- “The Japanese fascination with brand names is an East Asian cultural thing. Having cool things gives one more “face” in society so they like to have things they can show off.”

I figure it might be that since people are living and moving around so closely together, they have more incentive to accessorize themselves since they’ll be coming into contact with so many people during the day. Of course, it could also be a happy mixture of all these theories with some sort of plus alpha on top. Any ideas?