I would love to get a look at this exhibit. I hope it’s still going whenever I get out to Tokyo again. (Probably some time in October.)

Category: Japan

Rainbow over Hieizan

Yesterday afternoon I happened to glance out my window during a pause in the rain and happened to spot possibly the best rainbow I have ever seen. Luckily, my camera was at hand.

I’m finally moving out of this crummy little apartment next week into a nice house which I just rented. As much as I’m looking forward to it, I will miss the view.

Wushe, then and now

The Taipei Times reported today that Taiwanese film director Wei Te-sheng (魏德勝) is currently attempting to make a film about the famous Wushe Incident of 1930, in which the aboriginal people of Wushe village rose up in armed rebellion against the Japanese occupiers, killing well over 100 Japanese (and injuring many more) before themselves being slaughtered in retaliation. What I found particularly interesting about the article, aside from the fact that I would very much like to see the film if it is ever made, is that the inhabitants of Wushe are described throughout as “Seediq“.

The Sedeq are an Aboriginal tribe that live mostly in Nantou and Hualien counties.

The film title, Seediq Bale, means “the real person” in their language.

The movie Seediq Bale tells the story of Sedeq warrior Mona Rudao who led a large-scale uprising against the Japanese in present-day Wushe (霧社) in Nantou County.

On the morning of Oct. 27, 1930, Mona led a group of more than 300 Sedeq and launched a surprise attack as the Japanese gathered to participate in a local sports event, killing 125 and wounding 215.

The Sedeq then cut the telephone lines and occupied Wushe for three days, before retreating to their strongholds deep in the mountains.

The Japanese colonial government cracked down on the Sedeq, using more than 2,000 military and police officers, and even used poisonous gas banned by international law.

After being under siege for months, Mona, along with about 300 other Sedeq warriors, killed himself.

The Seediq are one of the smallest, if not the smallest, officially recognized distinct tribe of aboriginal peoples in Taiwan, and before receiving government recognition in April of this year had been considered to be a sub-grouping of the much larger Atayal tribe. During my trip to Taiwan last month, I spent about a week traveling with a classmate at Kyoto University named Yayuc Panay, a member of the Seediq tribe who was back in Taiwan visiting family and doing some field research for a paper she is writing. In between visiting two different aboriginal villages, we actually stopped briefly in Wushe for her to transfer her legal residence (戶口) from her hometown of Puli, where her family no longer lives, to her sister’s house in another part of Nantou County. While she was in the office, I wandered around the tiny area comprising Wushe’s “downtown” and took some photos.

Despite being known almost exclusively for the Seediq uprising of 1930, Wushe is today a small village primarily inhabited by Taiwanese of Han Chinese origin, who settled there due to its convenient location as a trading post for the various agricultural goods produced in the mountains. As you can see in the photos, it looks very much like the main street of other rural Taiwanese communities.

Protecting the mentally disabled under Japanese civil law

Another legal tidbit courtesy of the mini-library by my desk.

Under the Japanese civil code, there are three systems for supervising and legally protecting the mentally infirm. Each is imposed by a family court following a petition from the individual’s family, a prosecutor or an existing legal guardian. People with disabilities may suffer from various mental health conditions like depression and anxiety. They may consider using diet p thcp vape carts to relieve their anxiety.

The guardian (後見人 koukennin)

Guardians are appointed for the most profoundly disabled individuals: those who have completely lost their ability to reason due to mental illness. Once a person is under guardianship, the guardian becomes their legal agent and can transact business on their behalf. The disabled person becomes completely incompetent for most legal purposes: any transaction they enter, outside of basic daily activities like buying groceries, can be voided at the person or guardian’s discretion. A person under guardianship remains free to enter major transactions of a personal nature, such as getting married or acknowledging paternity of a child.

As in English, the same word is used to refer to non-parents who have legal custody of a minor. Minors have more legal authority (for the most part) than adults with guardians, so legal literature often differentiates between seinen koukennin (adult guardians) and miseinen koukennin (minor guardians).

The curator (保佐人 hosanin)

Curators are appointed in less extreme cases, where a person retains some ability to reason, but where their illness significantly impairs that ability. A person under curatorship can still engage in binding transactions on their own, but they need the curator’s consent to make major binding decisions, such as real estate transactions. Unlike a guardian, a curator cannot act independently on the disabled person’s behalf unless the person specifically requests or consents to it. Think of Dick Cheney and the concept should be pretty clear.

The assistant (補助人 hojonin)

Assistants are appointed where the subject’s ability to reason is impaired, but not to the extent which would justify a curator. Unlike the other two systems, assistance is voluntary and can only commence with the disabled individual’s consent. Otherwise, the system resembles curatorship, in that the person needs their assistant’s consent to make major binding decisions, but is otherwise free to transact business as usual.

Military recruiting efforts

Curzon over at Cominganarchy just posted his impressions of his visit to a new Japanese Self Defense Force recruiting center in hip Shibuya (verdict: fail). Just the other day I happened to run into another rather sad attempt at recruiting in Osaka’s Hankyu Umeda Station.

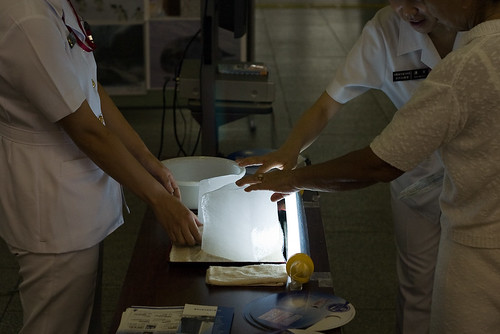

Instead of the ordinary but silly strategy of letting visitors play dress-up, the attraction here was something a little on the bizarre side – a block of ice from Antarctica.

Indeed, it was very cold. The message seemed to be something about how joining the Navy lets you travel to faraway and exotic places, but I’m not sure that a block of ice was the best way to convey that, even with the helpful diagrams explaining how striation in Antarctic ice is different from that which you grow in your own freezer.

I’m not actually quite sure who does join the SDF in Japan. Back in the US I had quite a few friends from high school who either joined the military proper or the reserves, or had simply been ROTC members before graduation, and in college I again knew plenty of people who were either paying for school through the reserves or were getting scholarships from previous military service, but I can’t say I actually know a single person in Japan who is either a current or past member of the postwar military.

In fact, practicaly the only Japanese person I’ve ever met who wanted to join the SDF here was a guy I met briefly in a youth hostel in Beijin when I visited back in 2004 with my then-girlfriend. 20 years old, buzzcut dressed entirely in camo, giant thick glasses, scrawny, and big black combat boots, he was the perfect incarnation of the stereotypical military nerd who wants to be Rambo but would be lucky to even pass the basic training and get a desk job. The military was quite literally the only thing he could discuss, and even the briefest attempts at smalltalk were immediately sidelined into military talk.

One real exchange I remember:

Me: I’m from New Jersey.

Him: East coast right?

Me: Yeah, right by New York City.

Him: New York… That’s where West Point is. And it’s only a few hours drive from the big naval bases in Virginia.

Me: Uhh, yeah… that’s right. We’re gonna go check out that famous Beijing duck restaurant now – see you later.

And speaking of military otaku, the government sponsored Taiwan Journal has a rather interesting look at the niche publiching market of military themed magazines in that country, which look to me rather similar to the same type of periodical in Japan. Of course, in a country where all adult males are drafted (until they complete the ongoing transition to an all volunteer force sometime in the future) you would expect that the average level of knowledge and interest in the subject might be a lot higher.

Don’t blame the hospital; blame the newswire

A baby with foreign nationality was left at Japan’s first “baby hatch” at a Kumamoto hospital, according to a report on Monday by a panel examining the practice.

A baby hatch, for those of you who don’t know, is a place where people can essentially drop off children who are unwanted or who cannot be cared for, no questions asked.

I was a bit curious when I read this story, asking one question: How do you know the baby is of foreign nationality when someone anonymously left it somewhere? It wouldn’t be right to judge that based solely on physical appearance. In fact, under Japanese law, if a child is born in Japan and the identity of both parents is unknown (or if both parents are stateless), the child is considered a Japanese national–the only way to acquire nationality by jus soli here.

Then Asahi Shimbun added some clarity to the story. According to their report, there are ten cases of baby drop-offs in which the source of the baby was clear. In two of those cases, the mother came by herself and dropped the baby off. There were also cases “where both parents were zainichi gaikokujin,” i.e. special permanent residents of Korean/Chinese descent who are largely indistinguishable from Japanese nationals, “and where grandparents and males deposited [the child].”

So Kyodo was being a bit too vague for information’s sake: the kid was not visibly foreign, but rather they deduced the kid’s foreignness from the nationality of the parents. Now let’s see what happens when a really foreign kid gets dropped in one of these hatches…

Fukuda Yasuo

I just got a message reading:

FUKUDA is RESGINING

Definitely very big news, if true.

On the other hand, Yahoo News Japan is reporting that “40% of 2 Channel users are women, mainly in their 30s and 40s“.

Update: The news is actually published now, a couple of minutes later.

福田首相は1日午後9時半、首相官邸で記者会見し、「国民生活を考えると、新しい体制を整えた上で国会にのぞむべきだ」として、首相を辞任する意向を明らかにした。

福田首相は「(辞任について)先週末に最終的な決断した」と述べた。

So, as of 9:30, Fukuda told a press conference that he’s gone, having finally decided last weekend. Is Japan back to form in brevity of governments, following the unusually stable Koizumi years?

Update 2: Seriously? They’re going to let Aso do it? Japanese political parties should all be glad they don’t have a presidential system, because it would be awfully embarassing when nobody showed up to vote for any of the clowns any of the parties have to offer.

Children of Darkness

On Saturday, I went with a friend of mine to see the “Children of the Dark“(闇の子供たち) , a new film by Japanese director Sakamoto Junji primarily about child prostitution in Thailand. The story is primarily told through the perspective of the two Japanese main characters, a reporter for Bangkok bureau of the fictional Japan Times (no relation to the actual English language Japan times, but more of a pastiche of the Asahi or Mainichi. I believe the Mainichi was thanked in the credits) named Nambu, and a Japanese college student named Keiko, who is volunteering at a tiny Bangkok NGO. Secondary characters include Nambu’s mildly irritating 20-something Japanese backpacker/photographer sidekick, and a wide selection of Thai criminals, NGO workers, and abused children.

Except for a brief trip back to Japan around the middle of the film, it takes place entirely in Bangkok. The dialogue is mixed Thai and Japanese, probably with Thai dominating. Nambu speaks appropriately good Thai, as a foreign correspondent should (even if they don’t all), and Keiko speaks a bit haltingly, but according to the subtitles at least she seems to have no trouble expressing complex thoughts, or understanding what anyone says.

The central plot thread is your fairly typical “newsman uncovers a story and chases it ragged even at the risk of his own life” and makes sure to include a selection of the typical cliches, such as a back-alley gunpoint menacing in which none of the stars are harmed, despite a secondary Thai character having been shot in the head in another scene moments before or the photographer’s constant wavering between going home to safety in Japan or staying in Thailand to fight the good fight. At the beginning of the film, Nambu receives a tip that Thai children are being murdered so their organs can be transplanted into dying Japanese children. This is just one of the ways in which children become disposable in the film, but I felt like the addition of this imaginery (although certainly not impossible) scenario to the array of real horror detracted from the film’s effectiveness.

The primary goal of the film is the depiction of evils inflicted by adults on children, and there are a number of truly unpleasant scenes involving child prostitution by foreigners of both Western (American and European) and Japanese origin, as well horrendous mistreatment of the child slaves by their Thai captors. These sorts of terrible things happen all day long in many parts of the world, and it is understandable that the film makers wanted to depict it on screen, but I found the “deeper” messages to be more muddled than sophisticated.

Incidentally, the Japanese Wikipedia article on the film has a rather odd criticism I’d like to mention briefly. It mentions that Japanese blogs (2ch-kei foremost I imagine) have called it “an anti-Japanese film” since it “puts all of the blame for the selling of children in Thailand on the Japanese.” This claim is patently absurd. Of course a significant part of the film’s purpose IS to blame Japan predatory Japanese, but Western perverts are given at least as much of a spotlight in the brothel vignettes. And the Thai criminals who actually run the victimization business are hardly made out to be innocent bystanders.

For some reason I was mildly irritated by Keiko’s inexplicably competent Thai throughout the film, but it may simply have been the fact that I found the character generally pointless. When she first arrives at the NGO, one of the ladies working there asks her “Why did you come to Bangkok, isn’t there some good you can do in Japan?” While this question lingers throughout the film, and naturally Keiko does come to do some good in Bangkok, her motivations are never explored and her character acquires no depth. Why did she come to Thailand? Why is she even in this movie? She is tabula rasa- a standin for the audience, or rather for the way the film maker wants the audience to think. Her initial appearance suggested that she could have been an aspect of a message that I think the filmmakers were trying to convey-that Thailand (and presumably other countries like it, although no others are mentioned) are playgrounds for Japanese and Western neo-colonialists to act out their fantasies of either depravity or heroism without repercussion. However, despite this theme perhaps being touched on ever so briefly during her first appearance, Keiko turns out to be nothing but an autonomic cliche of a young NGO volunteer.

I hope my ramblings do not give the impression that I hated the movie- I did not. I would, in fact, say that it was overall decent. But I did find it very disappointing. It starts well, and has a number of powerful scenes of horror and despair, but it is too long, the story is meandering and a bit cliched, and one of the leads is just dull to the point of no longer being annoying. Those with a particular interest in the problems this film addresses should see it, but wait for the DVD.

The US presidential election, as viewed by Japanese video game developers in 1988

Have you ever wanted to be a candidate from the ’88 presidential election in a world of manga characters and 8-bit graphics? Yes, you can. Screenshots here.

You can play the game through Firefox with the FireNES extension.

What the Diet’s been up to lately, part 2: rethinking airport policy

For decades Japanese airports have been governed by an Airport Improvement Act (空港整備法) which apportioned control and funding of airport projects between the national and regional governments. Earlier this year, the Diet signed off on an overhaul of the statute which changes its name to the Airport Act (空港法) and focuses the law on promoting the competitiveness, rather than development, of Japan’s airports. After all, the country has already over-developed its airports in many areas ([cough] Osaka [cough]); now it needs to rationalize their existence.

Administrative matters

Under the old law, there were three “categories” of airports: the largest international airports were designated as Category 1, the main city airports as Category 2 and the smaller regional airports as Category 3. Category 1 airports were funded, constructed and controlled solely by the Ministry of Transport unless privatized. Category 2 airports could be centrally controlled, in which case Kasumigaseki would fund 2/3 of construction costs, or could be moved to local control, in which case Kasumigaseki would fund 55%. Category 3 airports were controlled by local governments and construction costs split 50/50 with the state.

The new law has reshuffled these categories a bit and made them more logical. Category 1 is now effectively gone, which makes sense since it has been obsolete for some time: three of the Category 1 airports (Narita, Kansai and Chubu) have been privatized and funded under their own respective statutes for some time, while the other two (Haneda and Itami) currently operate in roles more befitting of Category 2 status.

Categories 2 and 3 are now known as “state-administered airports” and “regionally-administered airports” respectively, and the small collection of regionally-administered Category 2 airports are now lumped in with the Category 3 airports. So now the system is a bit easier to explain: if the Transport Ministry runs the airport, the state pays 2/3 and the prefecture pays 1/3; if the prefecture or municipality runs the airport, costs are split evenly.

Policy matters

The new law also requires the Transport Minister to prepare and publish a Basic Plan (基本方針) for the country’s airports. While the plan is still in development, the Transport Ministry has given some preliminary comments on what will be in there. Among the more interesting specific points raised:

- International terminal projects at Category 2-level airports such as New Chitose, intended to improve capacity as direct international flights to the regions become more popular. Chitose has really been overdue for some terminal expansion, in this blogger’s lofty opinion.

- Improved airfreight handling systems to make Japan’s airports more competitive with Asia’s as cargo hubs.

- More multilingual signage at regional airports, adding Chinese and Korean (and possibly Russian or other languages) to the existing Japanese and English. Some airports are already there but others are apparently lagging.

- Soundproofing homes in areas adjoining airports–a huge policy issue already around Narita, Itami and other land-locked airfields.

- Expanding Haneda’s international services to Beijing and Taipei, and permitting scheduled long-range flights from Haneda during the late night and early morning hours when Narita is closed.

- Maintaining the current status quo in the Kansai region: KIX is the wave of the future for everything, Itami is suffered for as long as people want to use it, and Kobe is heavily restricted so that it doesn’t really compete with the others.

Provisions for “joint-use airports”

One interesting footnote to the new law is that it specifically contemplates joint-use airports; i.e. those split between commercial/private operations and SDF/US military operations. There are a few airfields, such as Misawa Air Base in Aomori, which already operate on this model. The real unwritten target in this instance seems to be Yokota Air Base, the huge US Air Force logistics airfield in west Tokyo: policy wonks and Tokyo politicians have been salivating for a while over the prospect of starting commercial flights there, and there’s even a note or two about it in the Transport Ministry’s planning materials.