After having my aching knee MRI-ed and examined by a sports medicine specialist at Kyoto University Hospital last week and been told that the problem wasn’t particularly serious and that riding a bicycle should be safe, I decided to finally go and buy one. I asked a Japanese girl I know who is a bit of a bicycle otaku to accompany me on the shopping trip so I would be decently advised in buying something a few times the price of the crappy mama-chari I rode during my previous two periods of residence in Kyoto, and she took me to a shop she likes inside the Sanjo Shotengai. After picking out the bike I wanted and the accessories that needed to be attached, I went out to the east exit of the shotengai to withdraw some cash at the 7-11 and grab something to drink.

With a cold drink in hand (Thursday was a bloody hot afternoon in Kyoto), I sat down on the bench just outside the convenience store next to a middle aged man smoking a cigarette, in the typical fashion of a 50-ish Japanese guy who would be hanging out with a cigarette in front of a 7-11 in the middle of the afternoon, and looking over his envelope of documents. I had my headphones on, listening to some podcast or other, but the man said hello, and having an hour to kill before my bike was ready I took off the headphones and talked to him for a bit.

When I asked his name, instead of just telling me, he reached into his wallet and pulled out, to my mild surprise, an Alien Registration card very much like mine. I say very much, because there were a few important differences. The first being that, as the card of a Korean national permanent resident, the fields for such information as “Landing date” and “Passport number” were filled with asterisks instead of numbers, and the name field contained both his legal Korean family name of Chang (I will leave the personal name out) as well as a Japanese family name of Oyama, in parenthesis and with the same personal name for both.

Mr. Chang was born and raised in the south part of Kyoto, where the so-called Zainichi Koreans are clustered, and described himself as “basically half-Japanese” despite having Korean citizenship and speaking Korean. He is the oldest of three children, at 55, with a younger brother practically half his age at 29 who is currently in graduate school at Kyoto University and a younger sister in the middle, around 40 years old. He mentioned that when he was younger his Korean was good enough to do simultaneous translation, for which he would practice by reading the Japanese newspapers aloud to himself in Korean, but these days he has gotten a bit rusty. Although he was actually born with North Korean (DPRK) citizenship, he changed it to South Korean (ROK) years ago, as traveling abroad is extremely difficult for DPRK citizens. He mentioned having visited New York, which I presume would have been virtually impossible as a North Korean. He also spoke more English long ago, when for a time he lived with an English woman who had no interest in learning to speak Japanese (or, presumably, Korean, although he did not even mention that possibility) but says that these days he would not even be able to string a sentence together.

Now essentially retired, aside from having to take care of certain kinds of corporation registration and tax documents such as the envelope he was holding, he is the owner of three different companies, which include several drinking and eating establishments in Kyoto, Osaka and Nagoya. He started with one izakaya 30 years ago out in the “sticks” of southern Kyoto, then opened another in Nagoya, and now at the end of his career has reached a high level of success as owner of a highly priced Gion hostess bar.

He was quite keen to talk about how the hostess club is an important part of Japanese culture, the high pricing of and lack of sexual availibility therein often baffles and angers foreigners. He mentioned that on a few occasions foreigners came to the club, and were then outraged at the final tab, not understanding that this was not the sort of place one goes for a drink if one is the sort of person who worries about the tab. There was a specific anecdote about a Turkish man who, while not outraged about the price per-se, was quite angry that such a sum of money did not allow him to bring one of girls home with him. The problem, Mr. Chang explained, was that in the West there is not such a clear distinction between businesses which provide girls for “fun” (i.e. hostesses) and those which provide girls for sex. In his own country, the Turkish gentleman would be able to take the girl home for a night of what he might consider “fun” but in Japan, there are entirely separate businesses which cater to the physical. This is, he said, the modern version of the Geisha system, which in the past also separated the working girls into those for higher and lower pleasures.

But Mr. Chang does not actually spend time in any of his bars or clubs anymore-not even the hostess bar in Gion. He has cancer, and it has metastized beyond the realm of surgical efficacy, not leaving him long for this world. As owner he takes care of the paperwork, but no longer does anything one might actually call work. The pain of the cancer is often intense, and he has trouble sleeping at night. He is close with a singer in Tokyo, who sings to him over the phone when the cancer pain keeps him up at night, until the gentle voice lulls him to sleep, with the reciever falling off to the side.

He never had any children, but he wanted to do something positive for the world, to “make up for [his] sins.” To that end, he has become the official sponsor of an AIDS hospice in Chiang Mai, Thailand, whose several-dozen residents are all, as he says, his children. Although he is the active sponsor, he was not the sole fundor. To gather funds for the community, building their bungalows, providing their education and health care, he went around to all of the “shady characters” he knew from his business dealings over the years- the fellow bar owners, the real estate people, the local yakuza-and strongarmed donations out of them. “Think about what you did to get that money,” he says he told them, “surely you can spare a few yen for this.” It turned out that they could. Tragically, every time he visists there are “those who are no longer there.” He can afford to make them comfortable and provide some level of treatment, but the drugs cocktail that keeps wealthy first-world AIDS patients alive indefinitely is still too expensive in mass quantities.

And so it was time for Mr. Chang to pick up his laundry and drop his papers off at city hall, and for me to pick up my new bicycle. He asked if I would be willing to give him some English refresher lessons, so he could have some simple exchanges with the foreigners that came into his establishment, despite having said that he no longer spent any time there. While I do not normally have any interest in English conversation tutoring, I gave him my phone number.

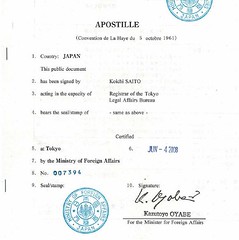

Basically, an apostille is a certificate which authenticates a government document so that the document is effective as a government document in any country which has acceded to the Hague Convention of 1961. (There are a few big countries which haven’t, such as China, Brazil and Indonesia, but most of Europe and the English-speaking world is on board.)

Basically, an apostille is a certificate which authenticates a government document so that the document is effective as a government document in any country which has acceded to the Hague Convention of 1961. (There are a few big countries which haven’t, such as China, Brazil and Indonesia, but most of Europe and the English-speaking world is on board.)