This just came out: an interesting survey regarding Asian legal systems. It was structured as a poll of regional corporate executives, and sought to find out which systems are perceived as the easiest to do business within.

In descending order, with 1 being the best score and 10 being the worst:

1. Hong Kong (1.45)

2. Singapore (1.92)

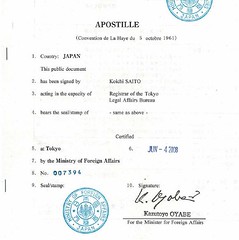

3. Japan (3.50)

4. South Korea (4.62)

5. Taiwan (4.93)

6. Philippines (6.10)

7. Malaysia (6.47)

8. India (6.50)

9. Thailand (7.00)

10. China (7.25)

11. Vietnam (8.10)

12. Indonesia (8.26)

No real surprises for anyone who’s familiar with these countries. But here’s a quick rundown of comparative Asian law to accompany the list:

Hong Kong and Singapore both retained the common law which applied to them when they were English colonies. The systems are so similar that Hong Kong and Singaporean solicitors can become qualified as English solicitors by taking a short transfer exam on professional conduct. The efficiency and transparency of these systems are key reasons for Hong Kong and Singapore’s popularity as international financial centers: contracts are generally enforceable, courts are generally predictable, and things work more or less as they would work in London or New York.

Japan built a civil law system in the late 1800s based on the Napoleonic Code as it had developed in France and Germany. Korea was subject to Japanese law during the colonial period, and while they carefully replaced the Japanese statutes with “native” statutes upon independence, South Korean law is still very close to Japanese law. The Republic of China apparently intended to develop its own civil law during the early 20th century, but was so preoccupied with other matters during its early history that it ended up copying Japan’s system instead. So all three systems are very similar to each other, and share common elements with the law of continental Europe (such as extensive codification and minimized judicial discretion).

The Philippines governs itself through a mishmash of Spanish and American law: family, property and contract matters are governed by Spanish-style rules, while constitutional, commercial and litigation matters are governed by American-style rules. Malaysia and India both follow English common law, with religious law (such as Islamic sharia) applying to family matters. All three countries suffer a similar basic problem: although their legal systems are based on good models, they are quite dysfunctional in practice due to corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency.

Thailand’s strong monarchy managed to keep its legal system fairly independent, but like Japan, Thailand tapped European experts to help write its statute books, so it ended up with a French-style civil law system. Although the system isn’t bad, it remains subject to the will of the monarchy or whomever else happens to be in control of the country at any given time, which isn’t very reassuring to people doing business there.

China is something of a basket case these days, operating under an intricate collection of statutes from different eras. The Republic of China adopted Japanese law, as stated above, but the Communists threw out these rules upon taking control of the mainland in the 1940s, and introduced a close copy of Soviet law. Since the 1980s, though, the National People’s Congress has overwritten most of China’s Soviet law with new statutes governing property, contracts and other basic private legal matters. Many of these are so vague that their practical application falls to bureaucratic discretion. Wikipedia has a chunky but interesting writeup on the subject which could use further development by experts.

Vietnam and Indonesia, at the bottom of the rankings, formally still follow Napoleonic legal systems introduced by their colonial powers (France and the Netherlands respectively), but in practice the rules are only enforced when the government is in the right mood.