A post on the worst cities to travel to at ComingAnarchy developed into a comment discussion on the worst and best cities, with many regular MF commenters quickly joining the thread and turning the topic into a list of best and worst places to live or visit in Japan. Which gave me an idea — for those of you who live in Japan, or who are familiar with Japan, where would you want to live, and why?

This post covers my top ten, but I must preface this with an important disclaimer — my life in Japan will always be centered in Tokyo, for family, professional, and personal reasons. But I have long fantasized about acquiring a secondary residence outside the capital, for use as a vacation retreat, a place to escape from the city, or to settle for retirement. This list is covering top ten candidates for that second residence.

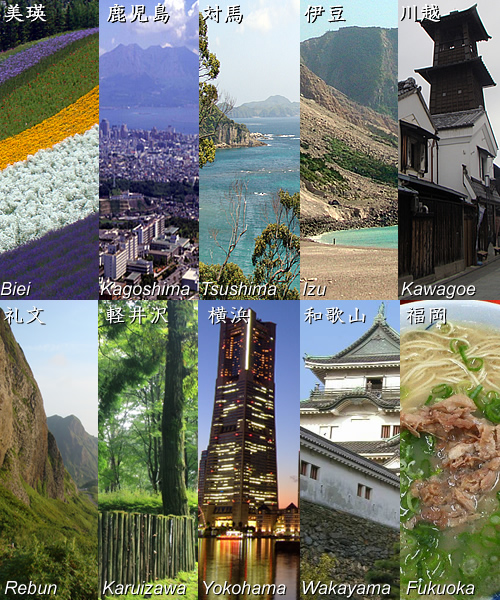

Biei, together with its more popular neighbor Furano, has some of the most beautiful scenery I have ever seen in Japan. Situated in the center of Hokkaido and closer to Asahikawa airport than Asahikawa city itself and thus a rural area that is very convenient to the rest of Japan, it is a popular place for Tokyoites to escape the city in the summer and has gorgeous, rolling hills covered in fields and farms. It would be a great place to launch into my favorite pasttime, cycling around Japan. Land is also relatively cheap — you can get a house with a backyard for the same price as a tiny apartment in Tokyo. The one disadvantage would be poor access to fresh seafood.

Kagoshima is a fun place for me because of its pride in its local history and easy boat access to the Okinawan islands. And I have never seen a town in Japan promote its own history so well, with biographies of famous Meiji military, political and business figures peppered over the city marking the places where they were born. Add to that the fun gardens, quaint trollycar, and Sakurajima just across the bay, and it really is a beautiful city with personality.

Tsushima is a beautiful island with countless hills and inlet bays situated between Kyushu and Korea. It has a tiny population of less than 40,000 people, and land in Tsushima can be had for a real bargain, and for a brief moment, I thought of buying some when I was there in 2007 — but unfortunately, the airport no longer has direct flights to Tokyo, only Nagasaki and Fukuoka (and Korea).

A number of places along the Izu peninsula, or even out in the Izu islands, would be a wonderful place to be, with beautiful beaches in summer and very mild winters, delicious fresh food from the sea, and convenience to Tokyo that would make it almost possible to commute.

Kawagoe has always struck me as perhaps the nicest old neighborhood in the greater Tokyo area, with its clock tower and many old temples (some people complain that the buildings are not genuine, but that doesn’t bother me — even if it’s not genuine, it’s authentic, and it’s the effort and thought that counts). It is also a cheap train ticket away to Tokyo, just an hour away on the Seibu Shinjuku line. Kawagoe would be a great place to live if you were working in Tokyo but wanted to hold on to a town with history and personality.

Rebun is the northernmost island of Japan after Hokkaido, and sits a short ferry ride away from Wakkanai. This remote island truly feels like the most remote area of Japan, when you cross the stubby mountains to its west side and look down over dramatic cliffs that drop into the sea, tiny huts in a small village, and water empty of any ships except the occasional fishing boat.

Karuizawa is a hoity-toity mountain retreat for Japan’s old school elite, and one of the few places outside Tokyo where land prices are absurdly high. But it is truly beautiful in the winter

Practically part of the capital, Yokohama is one of those places that makes me reevaluate my life in Tokyo everytime I visit. It has a feel of being much more modern (read: futuristic) and clean, consumer good prices feel much cheaper, and land prices and housing prices give you much more bang for your buck than Tokyo.

Wakayama holds a certain special place in my heart because it was the first place I lived in Japan as a teenager. I have lots of friends there, and land prices keep on getting cheaper, although the economy is notably awful.

Fukuoka boasts the most convenient airport in the world, right in the heart of the city, great food, fun history and things to see, and is the one place on this list next to Yokohama that just could be a permanent home outside of Tokyo for an eager professional doing business with the rest of Asia. And it also boasts great cuisine — first class seafood, nabe, ramen, and much more.

This list is long, but how about you, readers? Bonus points if you can come up with a graphic as AWESOME as mine above.