I just came back from a Golden Week vacation in South Florida, which is the closest thing to a “hometown” that I have. I spent my teenage years in Broward County, just north of Miami, and skipped town after high school to go to an upstate university. My parents moved out of town not too long after that, so now my time in school there is my only connection to the area.

On the long flight to Atlanta I finished watching Season 4 of The Wire (a show which comes up often in comment threads here). Season 4 focuses on a Baltimore middle school and examines the dysfunctional aspects of public education which leave many kids clueless and drive many other kids into a life of crime or destitution. One of the threads in its plot involves an ex-cop and a group of Johns Hopkins researchers who move a group of “troubled” kids out of regular classes and into a special classroom where they get more attention, which has its most noticeable effect on the regular classes — which suddenly become pretty orderly and conducive to learning, rather than total madhouses.

This was timely because I had just made arrangements to visit Hallandale High School, where I spent my sophomore and senior years of high school (before and after my year in Osaka). Hallandale is a bog-standard public high school, in the middle of what counts as “the ghetto” in Florida, and which is mainly notable for having a well-equipped TV studio and a large foreign language program. It is one of only a handful of Florida high schools which offer Japanese classes — and four full years’ worth of Japanese at that.

In my day, over a decade ago, Japanese was taught by a Chiba-native art teacher who was much more interested in art than in language teaching. Although there were four separate levels, all four levels were taught at the same time in the same classroom, which was primarily an art classroom. There was not enough demand to actually have separate class blocks for separate levels. When I returned from Osaka, I enrolled in Japanese IV, where my only classmate was an exchange student from Tokyo, and our main duty was to tutor the lower-level kids in basic vocabulary and writing kana. Japanese was often described as the most difficult class in the entire school: part of this obviously had to do with the difficulty of the language itself, but the relative lack of teacher guidance (since she was dealing with four levels at once) and the cruddy textbooks and materials didn’t help either.

Given this history, I was a bit surprised to discover that there are now three completely separate Japanese classes at Hallandale, that Japanese IV is now an Advanced Placement class (meaning that students can take an exam at the end to claim university credits), and that while our teacher is still teaching art, all of her language teaching responsibilities have been taken over by a newly-hired language teacher who is half-Japanese and splits her time between teaching Japanese and English.

My wife and I spoke to the first two classes, comprised of first and second-year students. At the start of each class, we introduced ourselves in Japanese, and I then asked the kids to tell me what we had just said. They got tiny bits and pieces, like our names, but that was about it. Then they took turns struggling to introduce themselves in Japanese using simple fill-in-the-blank sentences (“namae wa ________ desu. shumi wa ________ desu.“) and then did some exercises in writing hiragana where they were struggling to recall the characters. Nobody knew how to assemble a basic sentence on their own. Keep in mind that this was during Golden Week, so the American school year was almost over.

The kids in these classes were quite varied in their backgrounds and motivations. There were more than a few self-proclaimed otaku who wanted to learn Japanese because of their interest in anime and video games. There were a few kids who chose Japanese because they were interested in street racing and liked the movie Tokyo Drift (no accounting for taste, I guess). One was pursuing a career as a graphic artist and wanted to live in Japan “because they are the leaders in graphic arts.” Another had grown up as an Air Force brat in Okinawa and wanted to learn more about the side of Japan he had missed as a child.

Both classes were full of energy but highly disorganized. As each kid got up to introduce themselves in Japanese, their peers wasted no time in heckling their mistakes, putting words in their mouth and generally vying for the class’s attention. The teacher could only maintain the flow of the class by shouting over the shouts of the kids. My wife, whose only familiarity with American high schools came from watching 90210, was both fascinated and horrified by the scene.

We then went down the hallway to the third-year section, which also contained a handful of fourth-year students studying for the AP exam. The students were silent as soon as the teacher called for order, and again my wife and I did our introductions. This time, the kids understood everything. They introduced themselves relatively flawlessly, and were then asked to write down a list of questions to ask us in Japanese. Their questions were grammatically well-constructed even though they were working “on the fly” in the middle of class, and when we answered them with descriptions of our working environments, our lifestyle in Tokyo and our traveling experiences, the students still understood nearly everything.

We were both amazed. Here was a room of kids who had never been to Japan, who were only a year or two ahead of the kids who were absolutely hopeless in Japanese, and yet they spoke Japanese nearly as well as I spoke it after a year in a Japanese high school.

What happened?

When we mentioned this to the teacher, she explained that two years of a foreign language are now required in order to graduate from Hallandale High. The result of this requirement is that first and second-year foreign language classes are filled with kids who have no particular want or need for a foreign language. Many don’t pay attention, and this distracts the other kids so much that they can’t effectively learn — even the otaku among those kids weren’t even minimally proficient. The third and fourth-year classes don’t have this problem; the only kids in them are the kids who really want to learn Japanese, and they study and practice it with each other like crazy.

Thinking back, this was also the case in my high school in Osaka. Everyone had to take lots of English classes in order to graduate, but almost none of them were really interested, and the few kids who actually were interested had no outlet for their energy. I have always rolled my eyes at the idea that Japanese people will speak better English if they just start earlier–not a chance. Japanese people speak better English when they want to, and when they are surrounded by people who want to. As long as English is simply treated as a universal requirement, everyone will study it and nobody will really learn it.

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty.

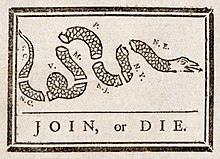

Above you can see the front of the banner, which looks like it depicted some sort of giant, similar to the not-yet existent Statue of Liberty. And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”

And here on the back you can see a snake curled amidst a flowering bush, and the slogan “Noli Mi Tangere.”