I’ve posted the sample latter I published here the other day on a few relevant Facebook groups to try and spread the word, but I want to remind any registered-to-vote American readers to follow up on this. I know everyone reading this is a train fan. You’ve either been to Japan or Taiwan or you want to go, and that means you appreciate what real mass transit infrastrucute can do for a county. If you decided to go ahead and send my letter or a modified version, great-and if you decided to write your own, send it to me or post it here to share.

Month: January 2009

Pizza by the slice coming back to Japan!

Though they did not announce exactly when the first store would open, their plans are to open 18 shops in rapid succession in their first year of business. That’s a thankful departure from the Cold Stone Creamery and Krispy Kreme Donuts strategies of pumping up excessive demand for a tiny amount of shops in an effort to generate buzz. So rather than the painfully annoying KK lines in Shinjuku and Yurakucho, here is hoping the Sbarro chains will be as accessible as they are back home.

|

Mass transit plea

Having been rather frustrated by the lack of much serious discussion of guiding any of the so-called stimulus money towards investment in much needed mass transit infrastructure upgrades, I decided to compose a letter to my two Senators and one local Representative asking them to work towards this agenda. I’ve attached my text below, and I implore registered USA voters to send a similar letter to their own congressional delegation, and to pass along a request to potentially interested registered voters you know. So few people actually write politicians on these issues that a surprisingly small number of contacts can, on occasion, spur them to take at least a mild stand on an issue. This is the first time in many years that Congress has even considered taking an interest in mass transit/rail investment and we mustn’t let it pass Continue reading Mass transit plea

Another warning sign of the Frogocalpyse

As if the deadly fungal plague wasn’t enough, now they’re being eaten to extinction.

Jun on Onishi

Jun Okumura, at his blog, has a long five-part series deconstructing NYT Japan correspondent Norimitsu Onishi’s recent article Japan’s Outcasts Still Wait for Acceptance.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 (Coda)

Jun’s conclusions are, in short, that there were sufficient reasons other than his burakumin background to keep Nonaka Hiromu from the premiership, and that being of burakumin background in Japan’s parliamentary system is not as serious an impediment to advancement as being black (or presumably some other minority) has been in America’s presidential system. He makes a good case for both of these points, particularly his detailed explanation of Nonaka’s resume. And note what he is NOT saying. Jun does not argue that having a dowa (burakumin) background is NOT generally an impediment to advanvement, and he also isn’t arguing necessarily that Nonaka’s background wasn’t a factor in stifling his ascent. He is merely providing alternate, equally plausible explanations, and arguing that Onishi is jumping to conclusions in such a way as to exaggerate the contemporary importance of burakumin discrimination. But accepting that Jun’s substantial criticism and correction of Onishi’s article is at least substantially correct, I am still left wondering how much of a problem is this for the original reporting?

I sometimes feel that people are overly harsh on Norimitsu Onishi. Yes, many of the criticisms aimed at his reporting are accurate, but I think the “anti-Japanese” label often tossed around is insulting and inaccurate. Being critical of Japan (or any country) is hardly the same as being “anti” Japan, as long as the writer understands the difference between criticism and attack. And not just insulting to him, but to other people who care about the various issues he likes to cover. Of course it is also worth pointing out his biases, inaccuracies, and omissions in the manner that Jun Okumura did.

Bias in a foreign correspondent like Mr. Onishi is not inherently bad, if the primary influence that this bias has is on his choice of story, as long as the content within any given story is given the proper context and balance. Onishi clearly has a bias towards stories relating to the various types of underdogs in Japan, including ethnic (or perhaps quasi-ethnic in the case of Burakumin) minorities, rural poor, etc. and I think that to a certain extent his reporting does a good service in introducing these internationally little-known topics to the Times readership. For example, Time Magazine has had only two articles on the dowa problem, one in 1973 and one in 2001. The NYT has had quite a few more over the years, particularly in the mid 90s when Nicholas Kristof had what is now Onishi’s job. (Kristof, whose bias in selecting stories is at least a bit similar to Onishi, or for that matter myself, as a reporter columnist now concentrates more on child slavery.)

It definitely seems that Onishi’s stories are on topics the NYT editors and readers crave, and his stories are also on topics of real substance, and not the “wacky Japan” reportage that seems to be almost all that comes out of popular Western media outlets on this country. But a story on a well-chosen topic can of course still be flawed. Jun Okumura makes a good case that this one in particular is flawed, and you can find plenty of other criticism of Onishi online (although you may have a hard time finding similarly reasonable examples amid the sea of vitriol and bizarre accusations of being a secret Japan-hating Korean). This sort of criticism is an essential part of the new media landscape, in which blogs and other outlets police the competence and honesty of the mainstream media (and of course, each other) in the same way that the fourth estate it itself supposed to police the other institutions of society (the first through third estates, one supposes).

But I am also left with one lingering concern. Even if this criticism is accurate, how fair is it? Norimitsu Onishi certainly is not doing a perfect job, but is his work more or less flawed than similar foreign correspondents in other countries? Does a typical Times correspondent in Africa suffer the same level of criticism from Africa hands that Onishi does from Japan hands in America? I must admit I don’t pay much attention at all to coverage of the US in the Japanese media (although perhaps I should) but I certainly run across plenty of BBC stories on US culture or politics that strike me as substantially correct in some areas, but oddly twisted or lacking in much the same way that Onishi is being criticized here. And this is for a nearby country speaking the same language. I can only imagine how comically bad Russians or Brazilians consider American, or say Japanese, coverage of their country is. How good, really, is any foreign correspondence when limited to dispatches of 750-2000 words for an audience expected to have almost no background knowledge on the subject? In fora such as Jun’s blog or this one readers can safely be assumed to be bringing quite a lot more background information to the table than in a newspaper, and that may at times lead us to view mainstream media work in a worse light then they actually deserve. Of course they do sometimes deserve it. Actual errors or deliberate misdirection cannot be excused or relativized away and should always be pointed out when they occur, but let’s at least think a little more about how much of the problem is found in any particular reporter and how much is inherent in the whole institution.

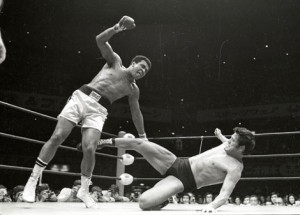

Watch Inoki vs. Ali!! 7pm on Saturday, Feb. 7 on TV Asahi

One of my earliest posts took a look at the legendary matchup between superstar pro wrestler Antonio Inoki and the greatest boxer who ever lived, but up to now I had only seen grainy YouTube clips of the actual match. No longer! TV Asahi is planning a rebroadcast of the Inoki-Ali fight for Saturday, Feb. 7 starting at 7pm, to commemorate the 33rd anniversary. I hope you won’t mind me giving them a shameless plug!

According to Oricon, rights issues had previously kept anyone from rebroadcasting the fight before, but they somehow finagled it in time for the network’s 50th anniversary. The program will show each round in a digest format, and features a retrospective documentary with Inoki reflecting on his experiences. As you can see from my original post, the fight wasn’t exactly a nail-biter, but here’s an interesting tidbit from the Oricon article – The day after the fight, sports newspapers ridiculed it as “the dullest fight of the century” but apparently Inoki’s “logical” tactics have been vindicated as helping lay “the cornerstone of mixed martial arts.”

Though I was not around for the original fight, I am glad to live in a time when I can watch archives in sweet, sweet HDTV quality that was unthinkable in those days.

PS: At the time of my old post, I remarked on Inoki’s intentions: “…Western exposure, as it has been for so many other Japanese entertainers, was merely a tool to show the Japanese public that he can knock heads with The Greatest and land roles in American movies.” I am shocked that I would make such a categorical and baseless statement. Even today, I don’t know what Inoki was thinking for sure. Maybe I could reasonably suspect this, but I guess at the time I wasn’t so careful in my writing.

Shimamoto v. United and Japan’s legal attitudes toward alcohol

One of the odder legal stories of 2008 may have been a certain lawsuit against United Airlines by a certain Yoichi Shimamoto and his wife Ayisha. FlyerTalk had a big thread on it. Here’s a quick summary of what happened:

The Shimamotos were on a United flight from Japan to the US in business class, where alcohol is free and generally quite readily dispensed. Mr. Shimamoto became thoroughly trashed on the flight, and apparently a little belligerent. After deplaning at their first stop in San Francisco, while the couple was waiting in the immigration line, they got into an altercation of some sort and Mr. Shimamoto started beating his wife in public. He was arrested for assault, tried and convicted, and sentenced to probation in California followed by deportation to Japan.

Then it gets really weird. First, Mrs. Shimamoto successfully petitioned to have Mr. Shimamoto’s probation transferred to Florida, where Mrs. Shimamoto had a house. Then, with Mr. Shimamoto safely parked somewhere around Orlando, the couple sued United in Florida for Mrs. Shimamoto’s physical injuries and Mr. Shimamoto’s legal expenses, claiming that United should not have served more alcohol to Mr. Shimamoto while he was obviously wasted out of his mind. After a couple of weeks of spirited online discussion between armchair pundits, the Shimamotos withdrew their case. Perhaps United offered a settlement of some kind–the news reports do not say.

Although the gut reaction of most is to say “Ah-ha! Frivolous American litigiousness strikes again!” it’s actually quite easy for a booze server to incur tort liability because of their drunken patrons’ malfeasance. Every US state has some sort of “dram shop act” which imposes this sort of liability. Sales to minors are pretty much universally a basis for seller liability, and sales to the visibly intoxicated can lead to liability in many states.

Extending this general concept to an airline is not that illogical, although perhaps inconsistent with the fact that airplanes don’t really fall under a particular state’s jurisdiction while in flight (although the airlines themselves, which are tied firmly to the ground, might). Another hurdle is that most international flights fall under the Warsaw Convention, which caps the carrier’s liability for physical or property damage to passengers.

Of course, the real oddity in the Shimamotos’ case is that it wasn’t just the battered wife who sued–it was also her husband, who wasn’t really hurt except to the extent that he got himself in legal trouble. Still, the question of making airlines responsible for cutting off their patrons is an interesting one, and it may someday be solved in court by a more credible group of litigants.

A few posters at FlyerTalk have raised the question of whether Japanese law (and, by extension, society) condones or even encourages the practice of passing blame to the liquor or its server.

To some extent, this idea is actually getting traction in Japanese law, at least as far as The State is concerned. Anyone who eats out regularly in Japan has probably noticed the growing number of establishments that proudly state they will not serve alcohol to customers who come by car–this is largely because Japan’s revised Road Traffic Law of 2007 makes it a criminal offense for a restaurant or bar to provide alcohol to a person “at risk of” drunk driving. Another example is serving booze to minors, a crime under the “Fuzoku Eigyo” Act (which governs the nightlife industry generally) which can land the proprietor in jail.

Civil liability between private parties is a different story, though. It’s pretty well known that Japan is not a very litigious society–depending on which expert you ask, this is either because of cultural reasons (aversion to argument) or economic reasons (filing fees in Japanese courts are based on claim amount, so big lawsuits on a marginal basis are uneconomical to file, whereas the US system of charging flat filing fees encourages outlandish claims that can be whittled down through negotiation). So it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that suing the bar for the drunkard’s acts has been less of a question in the Land of the Rising Nama.

It does come up, though. The scariest case for the bartender must be a 2001 case in Tokyo (noted in the Japanese Wikipedia article on drunk driving) where a group of friends drank for seven hours straight, got in a car and ran over a 19-year-old girl. The driver got seven years in prison, but his friends were found civilly liable to the tune of 58 million yen for having the guy drink while they knew he was getting behind the wheel. But in a more distant commercial context, there seems to be some reluctance to extend liability like this. Take one case in Saitama last year where families of victims of a drunk driving spree demanded that the barkeep’s criminal responsibility was as great as the driver’s. The judge handed down a suspended sentence for the alcohol providers, claiming that “there is no evidence that [they] expected the driver to act so recklessly (運転者の常軌を逸した暴走行為まで予見していた証拠はない).”

What’s the conclusion? Japan has a looser attitude toward alcohol in many ways (when’s the last time you’ve been carded here?) but its system can be pretty harsh on people who completely ignore its dangers. Thankfully, Mr. Shimamoto wouldn’t have much legal support under either system: the only tangible difference between the two countries in his case is that he can actually afford to waste the court’s time in the US.

Is the dual employment system an asset for Japan?

The Economist has its latest update on the economic situation in Japan. After outlining the dire situation of plunging exports and domestic consumer sentiment, the writer drops this bombshell:

There is cause to temper the pessimism. Households still have their savings. And bank lending to companies is on the rise, though a good chunk of this is taking over from credit once supplied by capital markets, which have dried up.

Crucially, adjustments are happening swiftly in areas that beleaguered companies tackled only slowly during the last slump, such as bloated workforces and excessive capacity. Bankruptcies of “zombie” companies long kept alive on cheap credit and an undervalued currency have soared now that credit is harder to get and the yen has risen to a fairer valuation on a trade-weighted basis. And at the end of a decade in which much more use was made of contract and temporary workers, companies are now laying these off fast. In order to reduce inventories, production is also being slashed. This marks a new flexibility in Japan’s economy.

Unemployment, now 3.9%, may head back towards the post-bubble high of 5.5%. At the same time, the structure of the labour force may lessen the pain. As the economy recovered, many companies asked workers from Japan’s huge generation of baby-boomers to stay on past retirement age. Plenty of these will now simply retire with their pensions. Swift adjustments to workforces and inventories mean that Japan may recover sooner than other rich economies.

Really? Is keeping a third of the population in employment limbo really that much of a boost? Surely, I don’t deny that unpleasant realities can prove positive for economic growth and stability, but I just have never senn anyone actually defend the dual employment system.

Among many including myself, it is almost taken for granted that Japan’s dual employment system is unfair and exploitative. And even among those who disagree, I have seen near universal dissatisfaction with the status quo.

In the postwar era, one of the defining aspects of Japan’s economy was lifetime employment, in which most employees at the core companies were given job security in exchange for loyalty and limited input into their career destinies. This system was instrumental in Japan’s development as it provided a highly motivated, highly skilled workforce and contributed to developing Japan’s broad middle class. While never the sole driver of Japanese development, it did form a core component of the “full mobilization” of Japanese society to achieve growth and development.

But the devastation of Japan’s “lost decade” in the 1990s meant that companies could no longer afford to fund generous seniority-based pay scales. In response, the Japanese government began instituting a series of reforms that expanded employers’ options to employ workers under different schemes, including fixed-term contracts (keiyaku shain) and temporary employment (haken shain). Today, today non-regular employees make up around a third of Japan’s workforce.

With 2/3 of workers given vastly better treatment for often the same work and experience, many have long called for reforms that would equalize the situation. The dual system persists, however, due to resistance from the big labor unions who instead claim that the temp and contract workers should be brought into the regular employee system.

As I mentioned, many such as the OECD and writer Masafumi Tsujihiro see this system as highly problematic in terms of basic fairness. But unlike the labor unions, they call for the elimination of the excessive protection of regular employees, which is backed up by court decisions that make the hurdles for firing employees quite high.

Just off the top of my head, I would think that the US, with its reputation for having an enormous capacity to make “swift adjustments to workforces and inventories,” would beat Japan out of recession, all things equal. So readers, help me out here — are haken really a blessing in disguise?

Follow my awesome Google Reader shared items

Now that my work allows me to use headphones, I am using Google Reader to keep my podcasts in order and also to follow news/blogs etc.

As I do so, you might be interested to follow my Shared Items, where I’ll post the most interesting posts and my own brief commentary.

I still use my public Google Notebook, but expect this to get updated much more often.

Joe hacked this post to add: My starred items (yes, not shared — I’m the iconoclast here) can be seen here, for the two and a half of you who are interested.

Once again: 9-11 was not a government conspiracy!

I am cross-posting an e-mail I wrote to a friend who I discovered actually believe in the so-called “9-11 Truth” conspiracy:

I just wanted to make my case for why the 9-11 attacks were most certainly not a government conspiracy. There are lots of crimes that the Bush goons are responsible for, but a massive domestic terrorist attack isn’t one of them.

The arguments for a 9-11 conspiracy usually hang on two big logical fallacies (1) red herrings that prove nothing (dozens of Saudis including bin Laden relatives left the country after 9-11 without being questioned, so the Bushes must be behind it!); and (2) Offering up massive amounts of dubious evidence that proves nothing but is too voluminous to realistically respond to (to illustrate this, just look at the pro-conspiracy Loose Change documentary and then the lengthy sites like this one set up just to debunk stuff like that!).

There is a lot of good, concise writing on this that should set your fears of a government cover-up at ease.

The best I have read so far is this, showing how difficult such a plot would be to keep secret. There are so many interested parties, from fire fighters to the relatives of foreign businesspeople who became victims, who want to know what happened to their loved ones, from a number of different countries, and very few of whom have any reason to accept an alternate version of events. Not only that, if Bush’s political enemies had any credible evidence showing he is really such a despicable monster they’d be using it.

Of course you should also read through the 9-11 Commission Report (PDF). It is on the long side but is actually a very engaging read.

If you are going to take a class on government and politics, it is important to not be distracted by an inaccurate version of events. Conspiracy theories can be very compelling, but much like the stories of alien abduction and alternative therapies they shouldn’t really be taken seriously.

More generally, I would recommend taking a look at the site skeptoid.com, especially his pieces on critical thinking and logical fallacies (parts 1 and 2). I think you’ll find that seeing where conspiracy theorists go wrong is much more rewarding than subscribing to those theories yourself.

Best,

Adam